Scientists often use “epigenetic watches” to measure biological aging, but what makes these watches work is not completely understood. Now, scientists have discovered a clue: watches are synchronized with random mutations that arise in DNA as we age.

For a long time it is known that, about human life, mutations accumulate in the DNA of cells. This happens when cells are replicated or exposed to insults, such as radiation and infection. In addition, with age, mechanisms that repair DNA damage do not work so well. As people age and mutations accumulate, the chances of immune problems, neurodegeneration and cancer also increase dramatically.

But DNA mutations do not tell the whole history of aging.

There are also molecular changes that take place “in addition to” DNA. These alterations, known as “epigenetic” changes, do not directly alter the underlying code of DNA. Rather, they turn on or turn off the genes or upload their volume up or down. The research suggests that the pattern of epigenetic markers in DNA changes predictably as we age, and epigenetic watches work by tracking those patterns and then estimating the “biological age” of a specific person or tissue.

The new study, published on January 13 in the magazine Aging of natureLink these genetic and epigenetic changes in a new way.

Related: Pregnancy can accelerate ‘biological aging’, the study suggests

“It’s an important study,” he said Jesse PoganikResearcher at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Medicine Instructor of the Harvard Medicine Faculty who did not participate in the investigation.

“People rightly criticize the so -called nature of the black box of epigenetic watches,” he told Live Science. There are many questions about what drives the epigenetic changes we see, and if changes in themselves really drive aging or are only a reflection of it, such as wrinkles are a sign of skin aging, not a cause.

“Any additional understanding of the basic mechanisms that are at stake, ultimately, will help us advance the field,” said Poganik.

A CASCADA OF CHANGES

The new study began with the senior study co -author Dr. Steven CummingsExecutive Director of the San Francisco Coordination Center at the University of California (UC), San Francisco, who theorized that genetic mutations may be directly linked to changes measured by epigenetic watches. And ultimately, “that is what we find,” said Cummings, who is also a senior research scientist at the Research Institute of the California Medical Center of Sutter Health.

“The two were very correlated,” he told Live Science.

To explain the reasoning behind this theory, we unpack some chemistry.

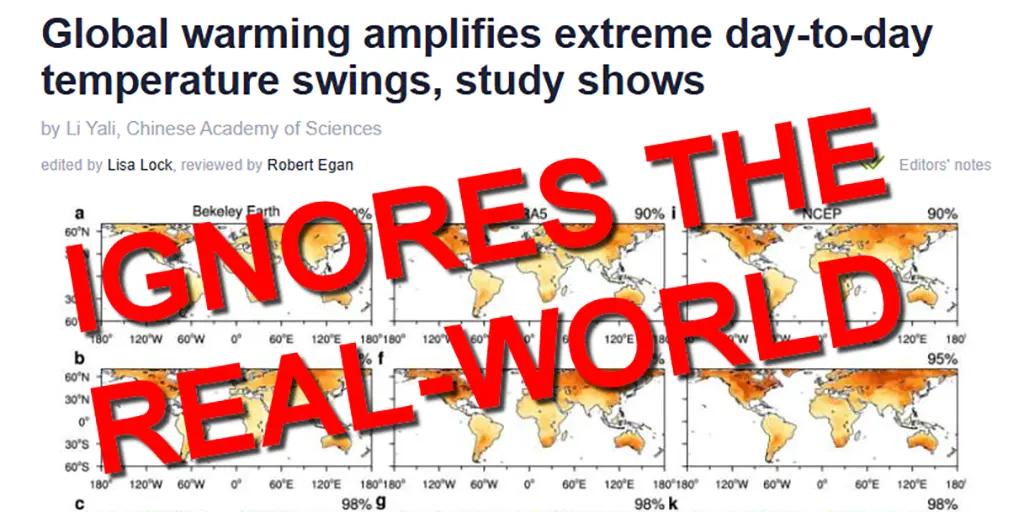

A common epigenetic mode, which based most epigenetic watches, is called DNA methylation. It implies molecules called methyl groups that adhere to cytosine (c), one of the four letters in the DNA code. This occurs mainly in places in DNA molecules where C is next to Guanina (G), known as CPG sites. But if there is a mutation and the C or G changes, that site is no longer CPG and, therefore, it is much less likely to get rid of.

“That is a way in which a mutation could cause a change in methylation, a loss of methylation,” said senior study co -author Trey IdekerProfessor at the UC School of Medicine San Diego and the Jacobs School of Engineering.

“And it turns out that the opposite could be true,” added Ideker. Methallation can, in turn, influence DNA mutations. If a methyl group joins a particular part of the C, this can cause a chemical reaction that destabilizes the CMaking it more likely to put later, Ideker explained.

Given this impulse and pull between mutations and methylation, the team wondered if they could link these interdependent processes to aging.

To do so, the main study author Zane KochA doctoral student in Bioinformatics at UC San Diego analyzed two existing databases: the Cancer Genome Atlas and Pan-Cancer analysis of entire genomes. From these, the team drew mutation and methylation data of more than 9,330 cancer patients. Most of the data come from tumor biopsies, but a subset of patients also had samples taken from normal and non -cancerous tissues. It is difficult to find comparable data sets with genetic and epigenetic data, said Ideker.

When overcoming the numbers, the researchers found that the mutated CPG sites had less methylation than the non -mutated CPG sites. In addition, the mutations seemed to coincide with a broader undulation effect: intact CPG sites located near these mutants were “surprisingly hypermetilled”, compared. And these undulation effects could be observed up to 10,000 letters on each side of the mutation.

“It’s like an explosion for change in methylation around that mutation,” said Ideker, but we still don’t know why or how it is happening, or the exact moment of what event happens first. “All we know is that this very clear relationship exists.”

Related: The new test of ‘biological aging’ predicts its chances of dying in the next 12 months

Seeing this relationship, the team built watches based on these patterns of genetic and epigenetic change, respectively. Both watches made similar predictions of age. In summary, the two watches seem to be synchronized.

What can this tell us about aging? It may be that genetic and epigenetic changes are occurring downstream of some other process that is actually the true driver of the underlying aging. However, Cummings favors a different theory: that DNA mutations drive aging and that epigenetics simply reflects this process.

If that is the case, scientists in the search to reverse or stop aging face a challenge. “They will have to discover how the underlying somatic mutations are reversed,” said Cummings, instead of adjusting epigenetic markers on DNA.

More research should be done to completely explain the studies of the study and their relationship with aging. To begin with, the current study only observed the fabrics of people with cancer, so the findings must be replicated in individuals without the disease, Poganik said. In addition, the tissue samples of each individual were taken in a time in time, so the team could not directly observe the changes that are developed with age, he added.

Ideker suggested that, in future laboratory experiments, scientists could trigger mutations in the cells and then monitor any epigenetic change that develops. Human long -term studies, which follow people over time, could also give an idea of what phenomenon it happens first, or if it is really a continuous interaction between the two, Poganik said.

Together, these future studies would throw a new light on what makes epigenetic watches work and, in general, which makes us old.

“Even developers and heavy watches users recognize that this is a limitation, which we do not understand how they work,” said Poganik. “The more we understand how they work, the more we will understand about the context to apply them.”

#Biological #aging #driven