When I need to get out of my head, I go to Ellwood. This stretch of cliffs along the coast in western schooner has trails through open grasslands and small roads that end up to a wide beach, where you can find forts of drift wood and views to the islands of the channel. At its northern end, an Eucalyptus brove is the home of the winter monarchs. I have happy memories of wandering the trees with a group of preschoolers in articles. When the sun crossed the clouds, dozens of the monarchs and their orange wings descended from the branches and quoted just out of reach. The forest felt, for a moment, touched by magic.

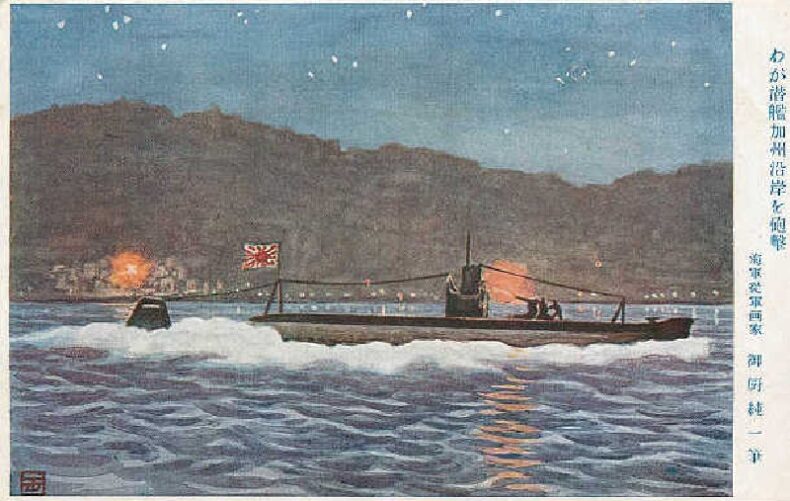

This is one of the things that makes it very difficult for me to remember that here, in 1942, the shells of a Japanese submarine were the only thing that flew over. After the attack, the Japanese imperial Navy reported that they had “left Santa Barbara on fire.” This was an illusion: the damage, at least for the earth, was minimal. The objective, the Ellwood’s oil field, lost a drilling and a bomb house. One of the shells crashed into a nearby dock.

But for those who lived on the coast and had just listened to President Roosevelt’s Firec chat when the bombing began, the fear caused by the attack was much more devastating.

A concern: the National Father’s Forest, just on the crest. Many firefighters, together with the team they used, had been away from this and other forests to fight in World War II. How could the forest service make everyday people more willing to stop the fires that no longer had the ability to fight?

Ellwood’s bombardment It was the brightness in the eye from which Smokey Bear was born. With a ranger and jeans hat, it has urged generations of forest users to take responsibility for avoiding posters and advertising places during the cartoons on Saturday morning, such as a giant balloon during Macy’s thanksgiving parade of MACY Thanksgiving.

But after decades of fire suppression, and increasingly devastating fires, some wonder if Smokey’s message could use an update.

One of these people is Emily SchlickmanProfessor of landscape and environmental design at UC Davis. Every time he left the mountains and back to the Central Valley, he saw an advertising fence with Ahumado, which still protected the dense rodal of forests that cover much of the Sierra Nevada.

Then, on a field visit to the Illilouette Creek basin in Yosemite, Schlickman saw something different. Instead of thick and protected forests or large dead wood supports, the valley full of a mixture of meadows, meadows and forests, the result of decades of Allow the fire to burn Through this area. “People say it is like a look at the past, such as what many of the forests of Sierra Nevada today should be,” she says. She remembers having turned to a colleague and say: “What would happen if Smokey had a friend?”

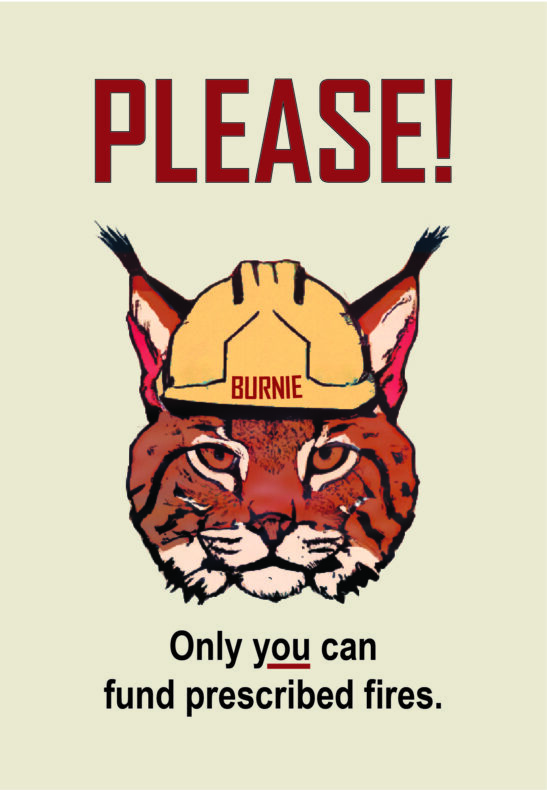

I found out about Schlickman and his work on my own trip outside the mountains. There was an advertising fence next to the interest 80: only you, he said in large white letters, you can decide our burning future. Next to the words was a mobile cat of pointed ears in a helmet.

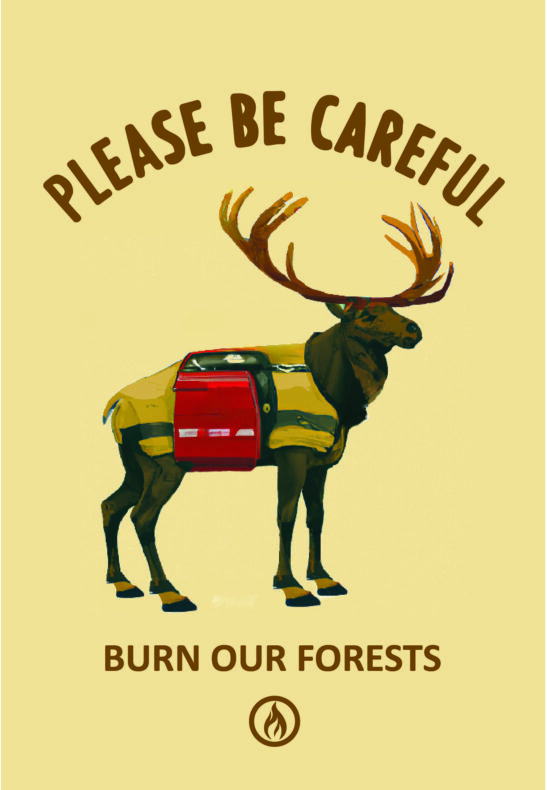

“Burnie The Bobcat” was one of several animals that Schlickman considered when looking at a pet for a more nuanced approach to fire. Through her work in landscapes and, more recently, as a member of the crew during prescribed burns, she says: “I began to see power, in many landscapes, to use fire as a beneficial force.” He began to look for creatures in the ecosystems prone to California fire that have lived with fire, including Tule Elk, Woodpeckers and Foxes.

Schlickman conducted a survey, and the Bob cat was the favorite. This particular fire pet also aligned with his desire to have a creature with generalized relevance. Mobile cats live throughout the state and throughout the country, although they generally avoid people and look for at night. (One of the few times I’ve seen one in the light of day was when I entered the brush to find a place to urinate; I was not the only one who looked at the path from the Chaparral that day). After a fire, the silly exchanges take advantage of the landscape exposed in a fire scar to look for squirrels, rabbits and rodents.

Burnie The Bobcat is the main spokesman for Considered Fire, but Schlickman also has other representatives, from Cinder The Coyote to Blaze The Bear, whom he considers Smokey’s sister.

Many of the animals that represent the beneficial aspects of fire are women, as well as many of the people in the prescribed and cultural cultural burns that Schlickman participates. “One thing that I am inspired by the beneficial fire is that so many incredible women are taking over,” he says. “For so long, suppression has been guided by really masculine and combative energy,” she says. “It is a great relief to be in a prescribed fire or cultural fire”, a place where people talk about fire like a living being, “because it is a completely different version.”

That does not mean that all the fires will be burned, or that there is something wrong with the mild panic that rises in me when the smoke begins to block the sun. In general, I feel relatively safe in the place where we live, near the coast, far from the narrow and winding mountain roads that have been threatened by fire here. But I also remember my hands sweating on the wheel when my children and I drove to the north in 2017, away from Thomas’s fire that was approaching, and the buzzing insistent in my chest when we stopped in the traffic along the road, with a small fire burning to the side of the road.

“Fire is scary,” Schlickman agrees, and not all landscapes benefit from frequent burning. Chaparral, for example, is burning much more frequently than its historical fire cycle, when 30 to 150 years could pass before an intense fire rolled through these depressed and low ecosystems along the costs and foothills of the state.

But the way people talk about fire is also important. Researchers found That after the bombing in Ellwood, nearby newspapers increased the frequency of language related to the most conservative fear and vocabulary, a change that researchers say it lasted long after the war ended. Smokey has also existed a lot of time. Perhaps a change is part of their future, with the help of a couple that can add a new perspective on fire fears. “There is a lot of trauma in the state around the fire, and I think it is important to heal and understand that the fire can be part of that healing process,” says Schlickman.

Now, walking through the Bluffs Ellwood, there are only a few signs that something happened here: a plaque in a golf course, a commemorative signal. Someone used the broken spring wood to build a local restaurant. Every year, the monarchs return, their wings as little flames.

*

Upper image: Cameron Walker

#Feel #burn