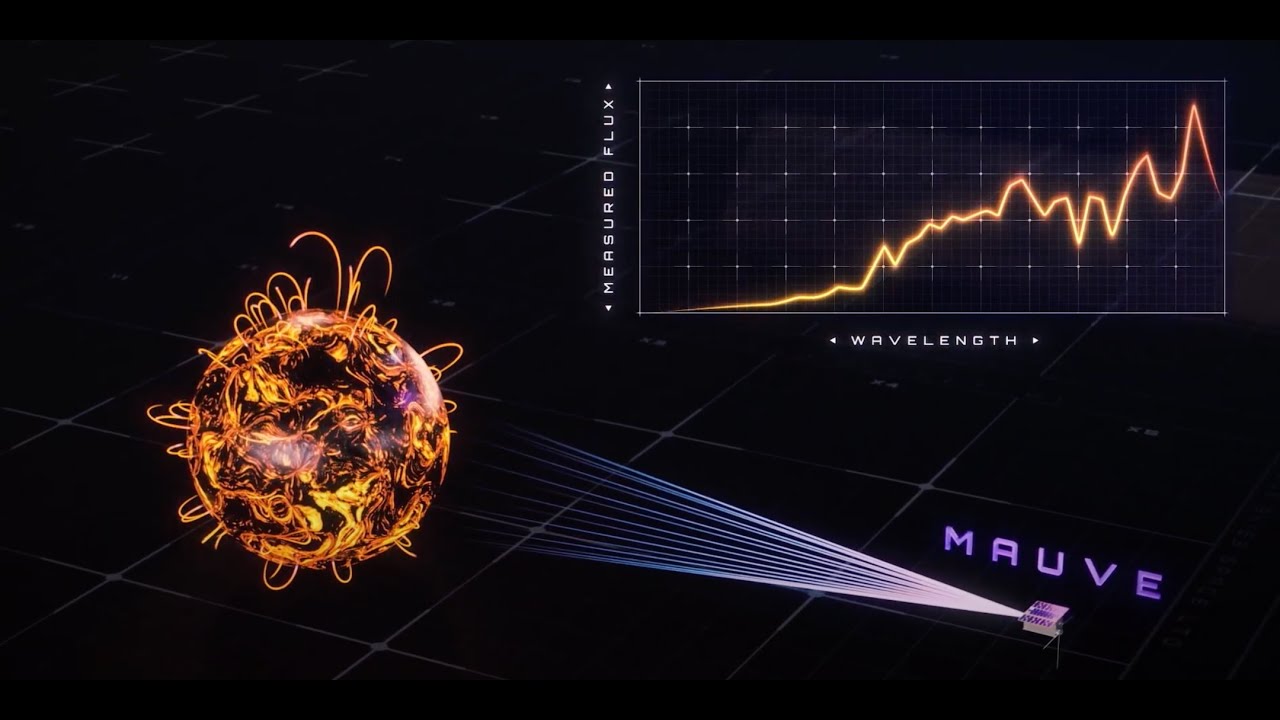

The world’s first commercial deep space astronomical telescope is set to search for stars that may host habitable exoplanets in their orbits.

The Mauve telescope, developed by London-based startup Blue Skies Space, is the size of a small suitcase and carries a commercially available ultraviolet spectrometer modified to monitor burning stars. It is one of the payloads that will be launched on SpaceX’s next Transporter-15 mission, currently scheduled for no earlier than November 2025.

Like our sun, other stars in the universe produce flares: flashes of high-energy radiation from dark, magnetically dense regions known as sunspots. Each flare sends a wave of energetic particles to the star’s surroundings. When such a wave passes over the Earth, the radiation, consisting of X-rays and extreme ultraviolet light, interferes with radio transmissions and causes blackouts. The flare also disturbs the ionosphere, the electrically charged layer of Earth’s atmosphere at altitudes above 20 miles. This interference affects the accuracy of the navigation and positioning signal from satellites such as the US GPS system.

But he the sun is not a very active star. Research suggests that many of their siblings are much more temperamental. The bursts of radiation produced by some stars are so intense and frequent that they practically burn any object in its vicinitypreventing any possible life from arising. By tracking the flare of hundreds of stars, Mauve will help astronomers select those most likely to host habitable exoplanets.

“The mauve color will allow us to understand the behavior of stars when they emit large amounts of energy,” Marcell Tessenyi, founder and CEO of Blue Skies Space, told Space.com.. “It will also help us understand what kind of impacts these stars could have on their neighboring planets. We will be able to understand which stars are likely to be harmful to the living environment and which would be benign.”

The last mission dedicated to observing stellar ultraviolet light, the International Ultraviolet Explorer, ended in 1996. The legendary Hubble Space Telescope can make such measurements, but the availability of observing time is limited, Tessenyi said. Hundreds of scientific teams from around the world compete for observing time on the veteran space telescope, carrying out a multitude of challenging astronomical research projects that cannot be accomplished by any other stargazing machine.

With scientific interest in exoplanets on the rise, Blue Skies Space decided to meet the growing demand for starburst observations with a small, low-cost telescope and sell the resulting data to scientists around the world through an annual subscription model.

“Space agencies do a fantastic job of delivering very high-quality space telescopes, but sometimes it can take a long time,” Tessenyi said. “And when these satellites are operational, like the Hubble Space Telescope or James Webb, people have to apply and hope to have the observing time they need. But not all science requires a very large, complicated satellite.”

With the low-cost Mauve (the company declined to reveal the exact cost of the mission), Blue Skies Space is pioneering a new approach to astronomical research from space. Although the new commercial space ethos of building satellites quickly and cheaply has dominated imaging of Earth from space for years, deep space astronomy has until now mostly headed in the opposite direction: trending toward more complex machines. worth billions of dollars.

Mauve, built in less than three years, is the first satellite launched by Blue Skies Space, although it was conceived after another mission, called Scintillationwhich is still in process. Twinkle, expected to reach space later this decade, is a larger satellite, weighing 330 pounds (150 kilograms of mass) and carrying an 18-inch (45 cm) telescope. Like Mauve, Twinkle will search for exoplanets around nearby stars and gather information about their chemical composition. But Mauve, Tessenyi said, will help researchers get closer to the most promising star systems, making Twinkle’s work easier.

Tessenyi said that despite initial skepticism among scientists about whether the new spaceway could work for astronomy, Blue Skies Space has seen a lot of interest in both missions. Nineteen universities around the world have already signed up to receive the data, which will begin being transmitted to Earth early next year.

Mauve will orbit Earth at an altitude of 500 kilometers (310 miles) for at least three years. If the project is successful, Blue Skies Space could add more satellites to its fleet in the future. The company is already studying the concept of a successor to Mauve, a more powerful UV observer, Mauve+.

“We fund the satellites up front, put them in space and once the mission is operational, we make the data available to users and over time we recover the cost of construction and operations,” Tessenyi said. “If the satellite is a success and we make a surplus, we reinvest it in our subsequent satellites and grow the company to deliver more satellites using this model.”

#worlds #private #space #telescope #find #stars #habitable #exoplanets