Coronal mass ejections (CME) are expulsions of plasma and large -scale magnetic field of the solar crown to the Helosphere. The magnetic field dragged into the CME plasma is crucial to understand its propagation, evolution and geo -ffectivity. Among the different observables in the radio wavelengths, the spectral modeling of the IMINCROTRON DIRECTRÓN (GS) emission (GS) of CME Plasma has been considered one of the most promising remote observation techniques to estimate the magnetic fields CME spatially resolved. Images of the CME GS emission of very low flow density near the Sun, which has orders of magnitude of greater flow density, has proven quite challenging. After the first detection and modeling of the broadly resolved GS emission of CME plasma by Batian et al. 2001There are only a handful of studies (Maia et al. 2007, Tun & Vourlidas 2013, Bain et al. 2014, Mondal et al. 2020) that they have managed to detect this broadcast.

This instrumental challenge has recently been fulfilled using the high dynamic image image of the Murchison Widefield (MWA) matrix. With solar images of spectropolarimetric wavelength of high dynamic range provided by the MWA, weak GS emissions of a CME to ∼8.3 solar radios are detected, the largest heliocentric distance reported to date. For the first time in literature, circular polarization detection (Stokes V) has been used together with total intensity spectra (Stokes I) to restrict GS models. We expected that the inclusion of polarimetric measurement would provide stricter restrictions in the GS model parameters. On the other hand, we find that homogeneous GS models, which have been used in all previous works, cannot model both total intensity and simultaneously polarized circular emission. This strongly suggests the need to use non -homogeneous GS models to stole the CME magnetic field and plasma parameters.

A brief description of the observations

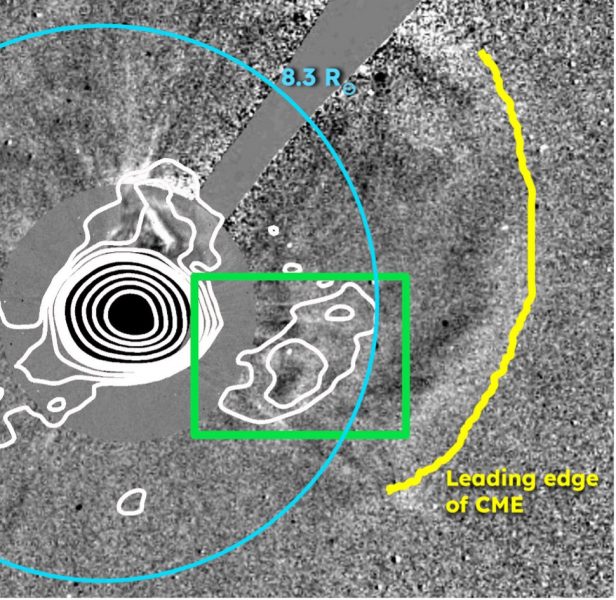

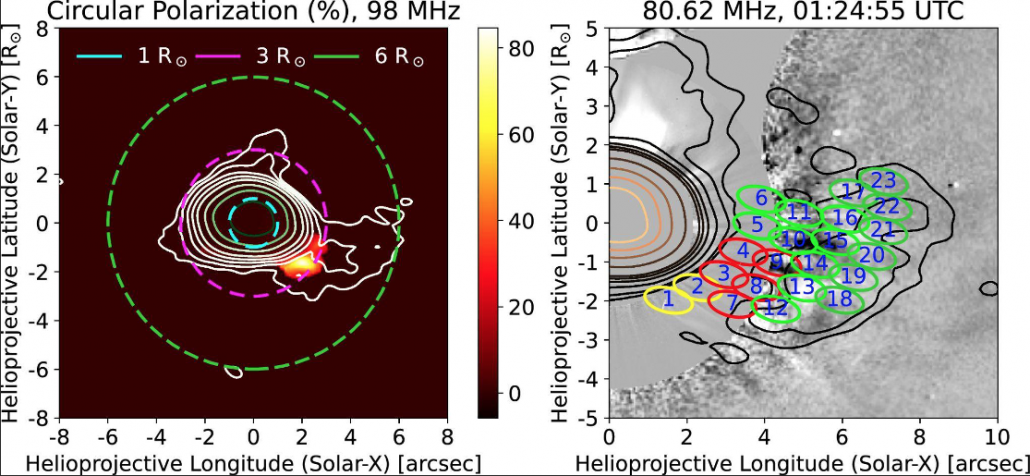

The CME studied in this work had a speed of the sky of around 490 km/s, but it was very weak in the Lasco Coronagraph images. This CME was reported as a partial halo event in the CDAW of Lasco. This CME emerged from the active region of the southwest (AR 12047), which was observed by the extreme ultraviolet images of the solar dynamics of solar dynamics on board (AIA). This CME spread towards the southwest. Radio observations were available that covered frequencies between 80 and 240 MHz using the MWA. Spectropolarimetric images of high dynamic rank provided by the calibration algorithm and latest generation images, P-Aircars (Kansabanik et al, 2022, Kansabanik et al., 2023a) Allow us to detect a weak GS radio emission to multiple frequencies. Interestingly, radio emission is detected behind the CME attack edge, which has raised the hypothesis due to local reconnections in the disturbed pre -existing streamer and the CME. The total intensity issuance (Stokes I) at 80 MHz is shown by superimposed contours in Coronagraph images of base difference in Lasco and C3, and the CME attack edge is marked by the yellow curve. The CME studied in this work is marked by the cyan box in Figure 1. The noise achieved in this image is close to the thermal noise limit of the observation (~ 1.3 times). This implies that there is little more to improve sensitivity by improving calibration or images. In spite of the high quality of calibration and images achieved here, the emission of Stokes V is detected only in a single spectral fragment at 98 MHz on a small CME patch (left panel of Figure 2). However, these observations place sensitive higher limits in Stokes V flow densities for other regions and spectral fragments. The inclusion of the detection of Stokes V and the strict upper limits of Stokes V together with the Stokes I spectrum allows us to study the validity of the common assumptions in the models used to model CME GS emissions.

Figure 1: Stokes and 80 MHz emissions are shown by the white contours superimposed in the image difference of Lasco C2 and C3 of the CME. Contour levels are at 0.5%, 1%, 2%, 4%, 6%, 8%, 20%, 40%, 60%and 80%of the maximum flow density. The radio broadcast marked by the Green Box is associated with CME and is the focus of this work.

Spectral modeling using a homogeneous source model

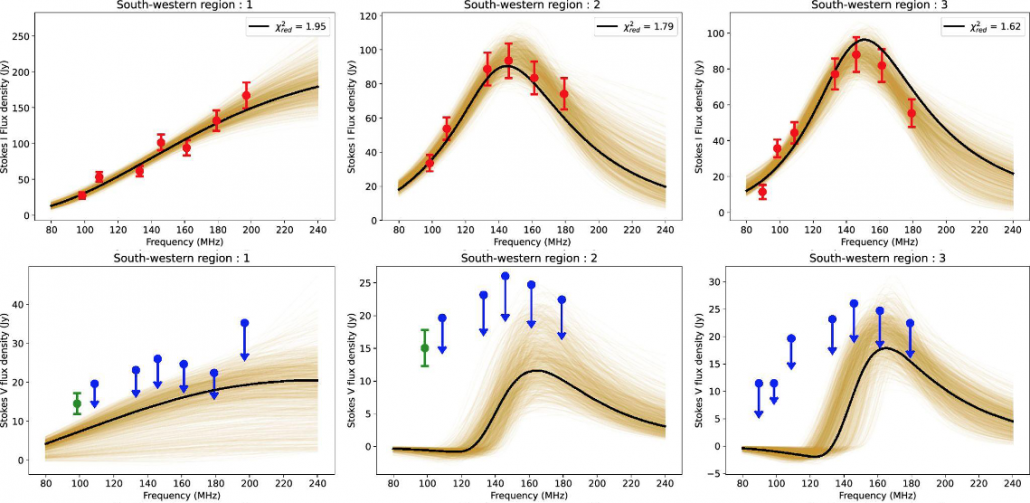

The weak radius emission GS of the CME is detected from 80 MHz to 180 MHz. The spatially resolved resolved spectra is extracted in multiple regions of function of function of indicate Independent Adjacent Point Point (PSF), marked by the ellipses in the panel Right of Figure 2. Stokes I of Pico (upper panel of Figure 3) confirms the emission mechanism as an emission of GS. The simplest GS emission model is a homogeneous and isotropic distribution of non -thermal electrons after a single distribution of the power law. To date, all the model emissions of CMS GS radio has been made based on this model (for example, Batian et al. 2001, Tun & Vourlidas 2013, Bain et al. 2014, Mondal et al. 2020, Kansabanik et al., 2023b). In our approach, the GS model parameters are limited to using a Markov chain (MCMC) chain of Monte-Carlo using both Stokes I spectra, Stokes V detections and strict upper limits.

Stokes I and V spectra observed and adjusted for some of the regions are shown in Figure 3. also shows GS spectra of 1,000 random realizations of the subsequent distribution of the GS model parameters. As is evident, the best adjustment models are consistent with the upper limits of Stokes I Stokes I and Stokes V, but inconsistent with the detection of Stokes V. In a situation like the present, where you can find a good model adjustment for Less restrictive data (Stokes V upper limits with Stokes i Spectra), but as restrictions become stricter (inclusion of Stokes V detection), it is no longer possible. To find a good model, it strongly suggests the need to critically examine the possibility of one or more of the assumptions made by the model that is violated. We examine the following key assumptions: restrict the distribution of electron energy to a single energy law, ignore any anisotropy in the distribution of non -thermal electrons hair and the assumption of homogeneity in the plasma present in the volume modeled by the model GS. To examine these possibilities and try to identify the specific assumption that is being violated, we systematically examine these assumptions.

Figure 2: Left Panel: Circular polarization image at 98 MHz. The background color map shows the percentage of circular polarization and the contours represent the emission of Stokes I. Right panel: regions of the CME where the spectra have been extracted. The red regions are those where the spectrum adjustment is made. Spectrum modeling is not performed for green regions. The spectrum adjustment is also done for yellow regions, which also have Stokes V at 98 MHz.

Conclusion

The synthetic spectrum analysis showed that among the multiple assumptions made in the GS model regularly used, the homogeneous plasma distribution and magnetic fields throughout them has the strongest effect on the Stokes V GS spectrum. However, with the limited limitations available for the best observations available today, it is difficult to limit a non -homogeneous GS model. Based on the results of the current instruments such as the MWA, there is no doubt that the spectropolarimetric image of even more sensitive bandwidth and wider of the next instruments, such as the Matrix Observatory of square kilometers that is expected to be available for ends of this decade, and the next very large matrix generation, and the frequency of the frequency of agile solar radio; Aided by the multiple point coronagraff observations will allow GS modeling to be used as a routine and robust remote detection technique to estimate the CME plasma parameters that cover a wide range of coronal heights.

Figure 3. The observed and adjusted spectra of some of the regions marked by red ellipses in Figure 2 using a homogeneous GS model. Stokes I spectra are shown in the first row. Stokes V spectra are shown in the second row.

Additional information

Based on a recent article by Kansabanik, D., Mondal, S. and Oberoi, D. 2024 APJ 968 55, https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ad43e9

Complete list of authors: Devojyoti Kansabanik 1,2,3Surjit Mondal4 DIVYA OBERO3

1 Cooperative programs for the progress of Earth System Science, University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, Co, USA.

2 The Applied Physics Laboratory of Johns Hopkins University, 11101 Johns Hopkins Road, Laurel, MD 20723, USA.

3 National Center for Radio Astrophysics, Tata Institute for Fundamental Research, Pune, India

4 Solar-terrestrial research center, New Jersey Institute of Technology, Newark, NJ, USA.

References

Bastian, TS, Pick, M., Kerdraon, A., Maia, D. and Vourlidas, A. 2001, Apjl, 558, L65

Bain, HM, Krucker, S., Saint-Hilaire, P. and Raftery, Cl 2014, APJ, 782, 43

KANANABIK, D., OBEROI, D. Y MONDAL, S. 2022C, APJ, 932, 110

Kansabanik, D., Bera, A., Oberoi, D. and Mondal, S. 2023a, Apjs, 264, 47

Kansabanik, D., Mondal, S. and Oberoi, D. 2023b, APJ, 950, 164

MAIA, DJF, GAMA, R., Mercier, C., et al. 2007, APJ, 660, 874

#indication #insufficiency #simplistic #homogeneous #models #estimate #magnetic #fields #CME #emission #turosincrotron #Devojyoti #Kansabanik #European #astronomer #radio #community