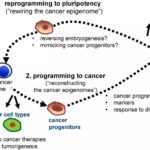

Genetic changes in genes are the main reasons for the formation of a tumor, also called tumorigenesis. In addition to genetic changes, epigenetic changes and reversible nongenetic alterations play an important role in tumorigenesis and disease progression. Since epigenetic changes can induce tumorigenesis and also reverse it, it is critical in cancer research to understand the epigenetic cellular reprogramming that occurs in various cancers, its role in disease progression, and explore the potential for its use in cancer therapy.

A comprehensive review article published by Dr. Jungsun Kim from the Department of Molecular and Medical Genetics, Oregon Health & Science University School of Medicine, Portland, USA, in the journal stem cell research, Highlights the history and advances in cellular reprogramming of cancer cells. Dr. Kim also draws attention to epigenetic changes during tumorigenesis and shares her perspective on how studying them can help us reprogram cancer cells.

Dr. Kim’s paper initially demonstrates evidence for cancer reversibility in mammalian embryonic cells through blastocyst injection, cell fusion, and nuclear transplantation experiments. These landmark experiments have established that oocytes/embryonic cells can restore accumulated epigenetic modifications and control the proliferation of cancer cells up to the blastocyst stage. Using human cells in mouse models, it has also been established that at later stages of embryonic development, especially during cell specification, epigenetic changes can be reactivated in a cell lineage-specific manner. These studies have paved the way for future research into the potential of cellular remodeling in cancer progression.

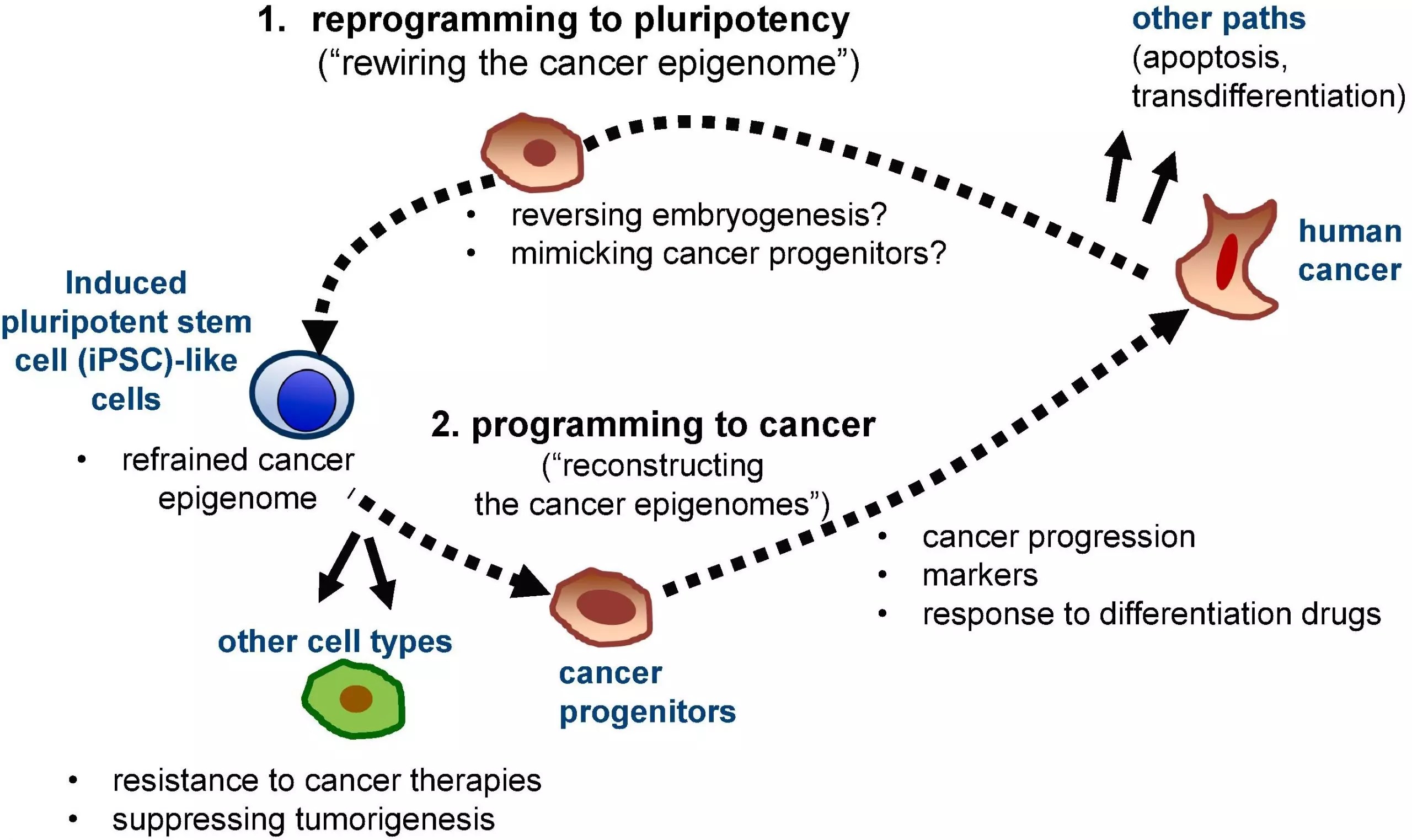

In addition to embryonic cells, somatic cells can be induced to reprogram into pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) by a set of master pioneer transcription factors (TFs), such as OCT4, SOX2, KLF4 and MYC which can control the expression of several genes in a cell. Models for various human cancers have been prepared using (iPSC). Modeling of human cancers using TF-mediated reprogramming of human cancer cell lines has demonstrated the potential of using reprogramming to study resistance or response to cancer therapies influenced by cellular states. TF-mediated cellular reprogramming in human cancer cell lines has also identified additional cancer-associated epigenetic changes responsible for the control of gene expression. Although epigenetic changes can be restored in programmed cell differentiation and suppress malignancy, some epigenetic changes are restored only in lineages corresponding to the primary cancer. Dr. Kim has utilized the potential of cellular reprogramming and provided a human cell model to study the early stages of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

Successful reprogramming of normal somatic cells using TF encompasses a large number of molecular changes. overexpression of OCT4, SOX2, KLF4 and MYC TFs induce highly dynamic chromatin remodeling, leading to the expression of silent genes in fibroblasts. Dr. Kim told Science Featured that “These chromatin dynamics translate into distinct phenotypes at very early and late stages, as well as reprogramming of intermediates that can follow diverse pathways through transient states.” Other studies conducted to understand the nature of these chromatic changes have shown that OSKM-mediated epigenetic changes are similar to changes observed during cancer development. In several types of cancer, important TFs are dysregulated, leading to epigenetic changes. Although the chromatic changes induced by cellular reprogramming are similar to the changes observed in cancer cells, pluripotent cells have a distinct and reciprocal epigenetic landscape of the cancer epigenome. This creates exciting possibilities for using cellular reprogramming to modulate the abnormal cancer epigenome.

The extensive review summarizes that a pluripotent environment can dominate the cancer phenotype, indicating that oncogenes can be reactivated during organogenesis. The ability to reprogram cancer cells to pluripotency and revert them to their original stage provides an excellent model for understanding epigenetic modification during disease progression.

“The biggest obstacles in cancer reprogramming arise primarily from the fact that tumors are very heterogeneous, yet only a subset of cells are reprogrammed,” Dr. Kim said. Solid tumors are made up of cancerous and non-cancerous cells, which show different cellular reprogramming capabilities. Cancer cells also have low reprogramming efficiency. Some epigenetic changes persist in cancer cells, and genetic mutations resist reprogramming the cells, preventing them from being completely reprogrammed.

Dr. Kim emphasizes that it is crucial to conduct more research on cellular reprogramming of cancer cells to understand the dynamic epigenetic changes during tumorigenesis to better understand disease initiation, progression, and therapy.

Magazine reference and main image credit:

Kim, Jungsun. “Cellular reprogramming to model and study epigenetic alterations in cancer.” stem cell research (2020): 102062. DOI: doi.org/10.1016/j.scr.2020.102062

About the author

Dr. Jungsun Kim, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor

Dr. Jungsun Kim is an assistant professor of Molecular and Medical Genetics at the Knight Cancer Institute and the Advanced Cancer Early Detection Research Center at Oregon Health & Science University School of Medicine. He received his bachelor’s and Ph.D. in biochemistry from Hanyang University in South Korea under the mentorship of Dr. IL-Yup Chung and completed postdoctoral studies at the University of Pennsylvania under the mentorship of Dr. Kenneth Zaret.

His laboratory studies the molecular mechanisms of cellular reprogramming and programming in cancer.

#Cellular #reprogramming #potential #model #study #disease #progression #cancer