Type II radio bursts are generally observed below 400 MHz with narrow, slow-drifting fundamental and/or harmonic bands. Events with initial frequencies above 400 MHz are rarely reported (e.g. Pohjolainen et al. 2008). Such high-frequency type II may arise from the interaction of CMEs with surrounding dense structures in the corona, such as streamers, ray-like or loop-like structures, or from sources in the lower corona.

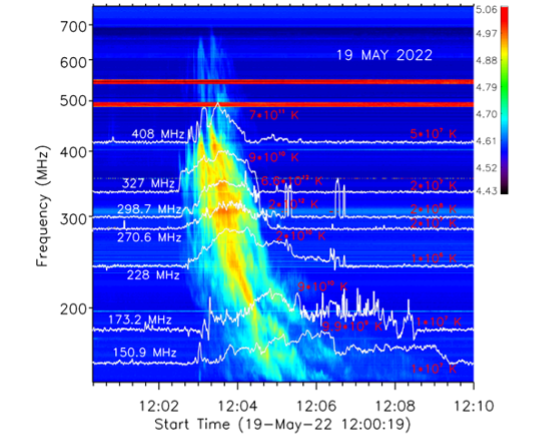

Figure. 1. Dynamic spectrum of the high-frequency broadband type II burst recorded by the ORFEES radio spectrograph (670 – 144 MHz). Maximum brightness temperatures (TBmax) at different NRH frequencies are represented with white lines.

Here we report an unusual type II broadband high-frequency burst on May 19, 2022 with an initial frequency of up to 670 MHz and an instantaneous bandwidth of up to 300 MHz, as recorded by the ORFEES spectrograph (see Figure 1). This bandwidth is much wider than that of typical events. Also, at any specific frequency, the burst lasts 2 minutes. They are also much longer bursts than usual. For this event, simultaneous observations of extreme ultraviolet radiation (EUV) and radio images from the Nançay Radio Heliograph (NRH) are available. This allows us to measure the location of the radio sources above the EUV shock structure and explore the cause of the high-frequency broadband feature.

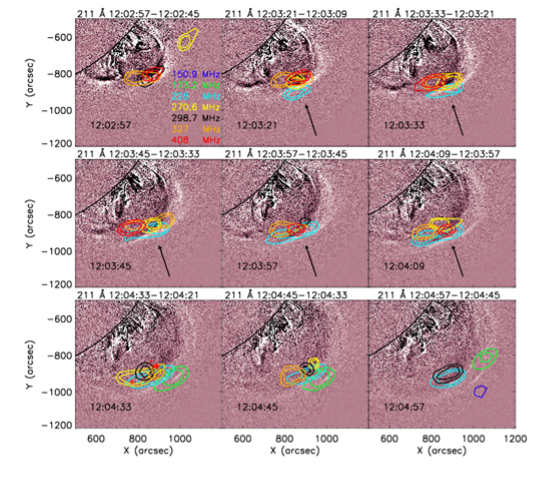

By overdrawing the 90 and 95% T contoursBmax In the AIA 211 Å running difference images closest in time (see Figure 2), we made four observations: (1) the type II sources are cospatial with the leading edge of the EUV shock wave structure (they are slightly separated, by 0.01 Rʘ; (2) the sources basically overlap each other before 12:04 UT (no spatial separation 0.001 Rʘ; later they disperse spatially and the lower frequency sources move further away from the disk; (3) as already mentioned, sources at several frequencies appear simultaneously and are distributed within a wide region of 150 ̶ 200 arcseconds; and (4) during most of the time of the outburst, the sources are spatially dispersed but still centered around the dip of the shock front that corresponds to the transit of the CME shock through the tops of the bright, dense loops.

Figure 2. Temporal evolution of NRH sources superimposed on the closest AIA 211 Å images in time. Radio sources are represented by 90% and 95% of T.Bmax contours.

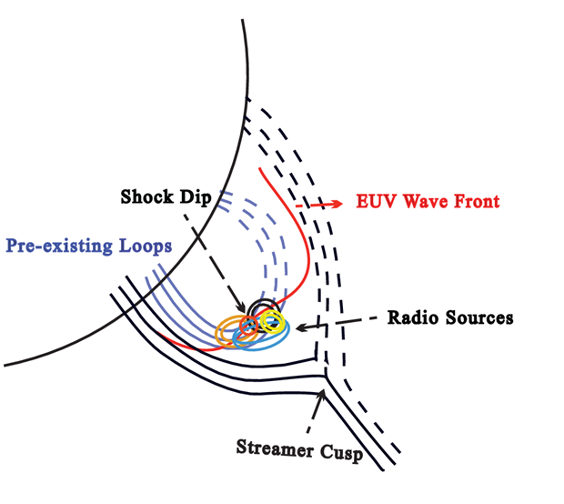

The drop is likely due to strong compression caused by shock propagation in bright, dense loops where the Alfvénic velocity (as well as the shock velocity) is relatively low. According to the EUV and white light data, the bright, dense loops connecting the two points are spatially correlated with the shock decay, indicating that the shock has transited through them with a strong interaction. In this case, the acceleration of electrons is quite efficient according to numerical simulations by Kong et al. (2015, 2016). We suggest that the type II burst originates from the transit of the shock through these magnetically closed loop structures that forms the shock decay (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Sketch of the shock loop system with the dipping region and corresponding type II radio sources.

The broadband characteristic of the type II burst means that the sources come from a region with a wide range of density; Either the density fluctuations of the source have large amplitudes or the source extends over a large and very inhomogeneous region. Our observations favor the latter scenario: that the type II broadband burst arises from broad sources centered around the decay of the shock.

We suggest that the explosion represents the harmonic branch, since the fundamental experiences a much stronger scattering/absorption effect and for many other coronal explosions the harmonic branch often represents the stronger one. At 12:03:41 UT, the upper and lower frequencies of the burst are 440 and 180 MHz, respectively. Thus, the densities within the type II source at 12:03:41 UT should vary from ~109 at ~108 centimeter3with a ratio of ~10. This is much larger than any possible compression ratio of a magnetohydrodynamic shock, indicating that the broadband feature is not due to density variations across the shock layer. More studies on similar events are needed for a deeper understanding of their origin.

Based on a recently published paper: V. Vasanth, Yao Chen and G. Micahlek, Awide-band high-frequency type-II solar radio burst, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 2025, 720, A15. DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/202554430

References

Kong, X., Chen, Y., Guo, F., et al. 2015, ApJ, 798, 81

Kong, X., Chen, Y., Feng, S., et al. 2016, ApJ, 830, 37

Pohjolainen, S., Pomoell, J. and Vainio, R. 2008, A&A, 490, 357

*Full list of authors: V. Vasanth, Yao Chen and G. Micahlek

#highfrequency #broadband #type #solar #radio #burst #Vasanth #Community #European #Solar #Radio #Astronomers