There has been a bit of lash On the issue of the MENOC deceleration lately, since the AMOC is “on the verge of collapse” to being “more stable than was thought.” AMOC, of course, refers to the circulation of southern flights of the Atlantic, one of the main oceanic circulation systems in the world that keeps the North Atlantic region (including Europe) exceptionally warm by its latitude. So what is this punishment about?

As is the case with such a penalty, there is not much scientific substance behind him, except for the small usual incremental steps in the search for better understanding. It is rare that a single article defeat our thinking, although the reports of the media unfortunately give that impression. Real science is more like a huge puzzle, where each new piece adds a bit.

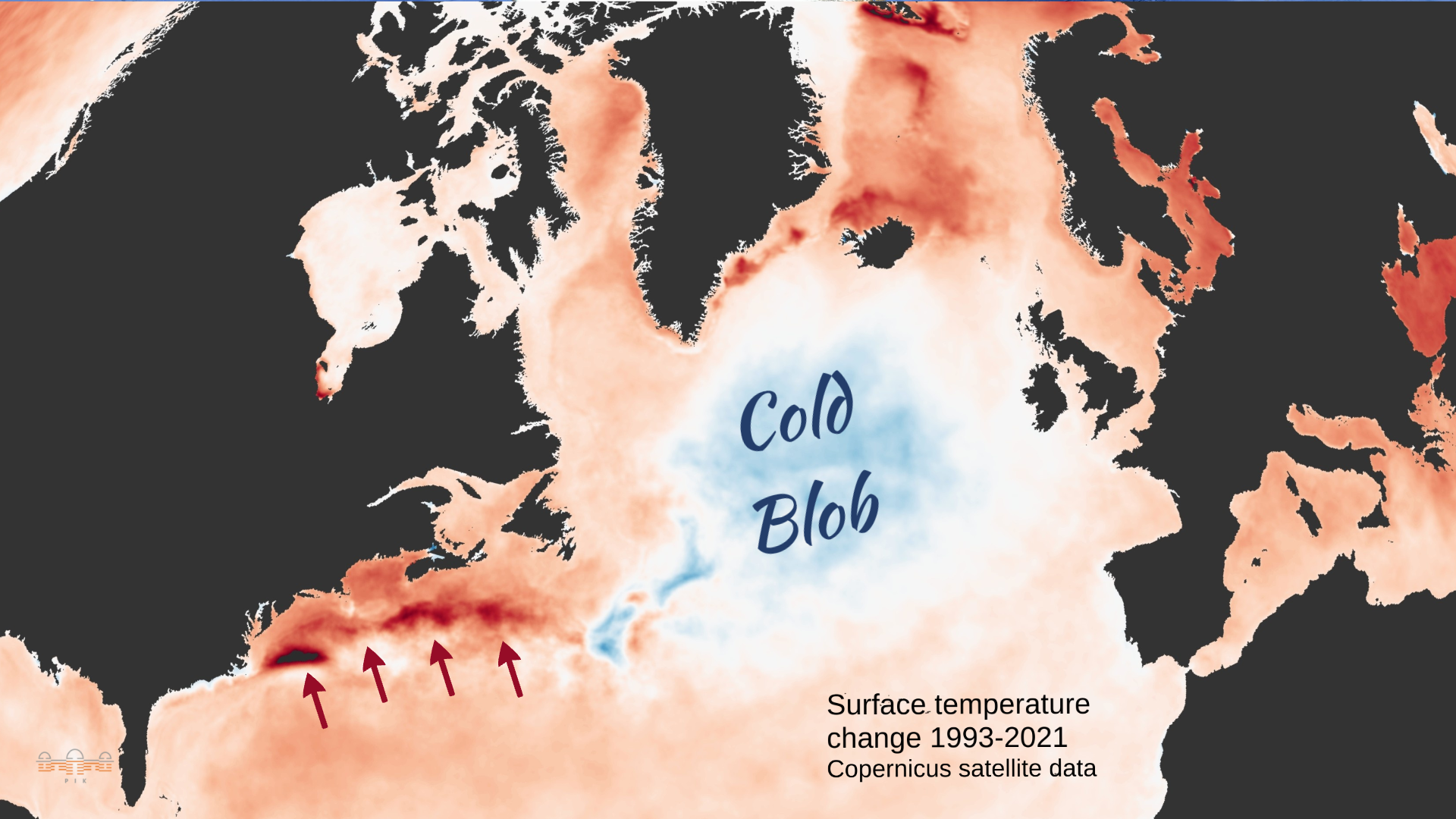

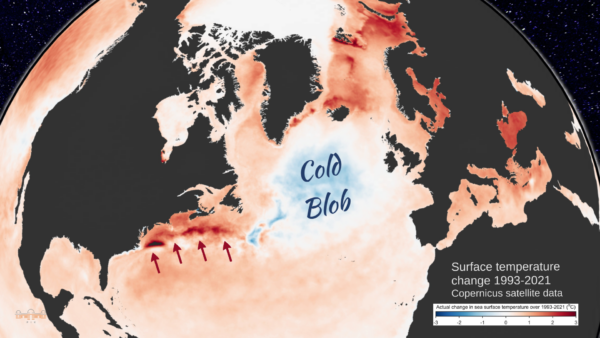

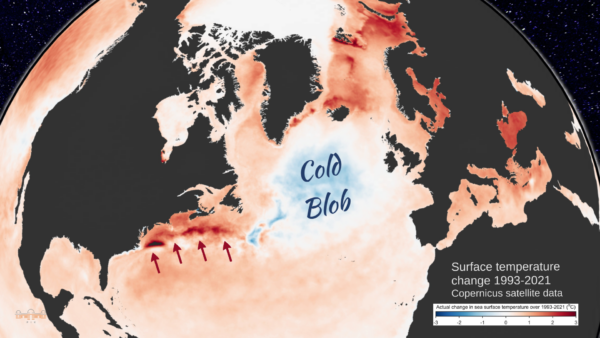

The last new piece is a new reconstruction of how the AMOC has changed in the last 60 years, for Jens Terhaar and colleagues. The background of this discussion are relatives for our usual readers (otherwise, only ‘AMOC’ enters the real search field. Fast projectTherefore, for the early days we need to use indirect clues. One of these is the surface temperature of the ‘fingerprint’ sea of AMOC changes as discussed in our document César et al. 2018 (Fig. 1). There we use the cold stain temperature anomaly (Nov-Mayo) as an index for AMOC resistance. Other studies have used other temperature or salinity patterns of the sea surface, as well as proxy paleoclimatic data (for example, sediment grain sizes), and generally found a decrease in AMOC since the nineteenth century overcome by some decadal variability. The new document criticizes our reconstruction (that is, César et al) and suggests a new method that uses surface heat flows from reanalysis data as an indicator of the AMOC resistance.

There are three questions here.

1. Does the ‘cold stain’ work well as an amoc indicator?

We had tried that in the historical races of 15 different climatic models in César et al. 2018 (Our Fig. 5) and discovered that it works very well, except for two atypical models that were known that they did not produce a realistic AMOC. Now Terhaar et al. He redidated this test with the new generation of CMIP6 models and discovered that it works less well, that is, uncertainty is greater (although for future simulations where AMOC shows a significant decrease in the models, our AMOC index also works well in its analysis) .

What the question raises: What models are better for this purpose: CMIP5 or CMIP6? One might think that the newest models are better, but this does not seem to be the case of CMIP6. Regardless of the AMOC, the CMIP6 models created a substantial controversy when their results came out: the climatic sensitivity of a subset of ‘hot models’ was too high, these models did not reproduce the evolution of the past temperature well (compared to the observed data) , and IPCC made the unprecedented movement of not presenting future projections as a model of model/less simple model, but instead used the new concept of “Evaluated global warming“Where the models are weighted according to how good the observation data reproduces.

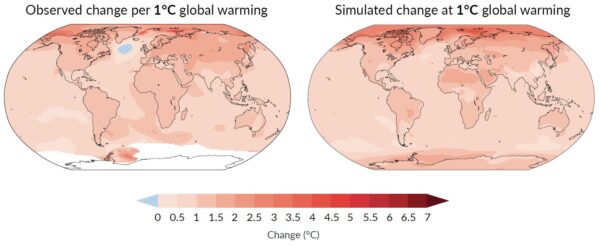

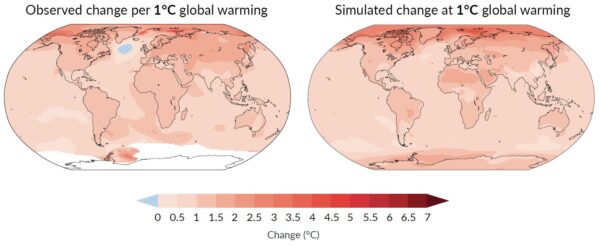

In the North Atlantic, the historical careers of the CMIP6 models on average do not reproduce the ‘cold stain’ despite the fact that this is such a surprising characteristic of the observation data, as clearly shown in the summary of the political leaders of the political responsible for the IPCC AR6 (see Fig. 2 below). Of the 24 CMIP6 models, a complete 23 underestimate the cooling of the sea surface in the ‘cold spot’. And most CMIP6 models even show a strengthening of the AMOC in the historical period, that previous studies have proven to be linked to the strong aerosol forcing in many of these models (for example, Menary et al. 2020, Robson et al. 2022). The historical evolution of the temperature of the northern hemisphere in the models with a strong aerosol effect “is not consistent with the observations” and “simulate the incorrect sign of the salinity trends of the surface of the sub -elotic north Atlantic”, such as Robson et al . write. Therefore, I consider that CMIP6 models are less adequate to prove how well the ‘cold stain’ works as an AMOC indicator than the CMIP5 models.

2. Is the new AMOC reconstruction method, based on the loss of heat of the surface, is it better?

In CMIP6 models it looks like this, and the link between the transport of AMOC heat and the loss of heat from the surface to the north makes physical sense. However, in the models the heat loss of the surface is known perfectly. In the royal ocean that is not an observed amount. The simulations of models, the so -called reanalysis should be taken. Although these simulations assimilate the observation data, in most of the ocean surface they are basically temperatures of the sea surface, but the loss of heat of the surface also depends on the air temperature, the wind speed, the Moisture, radiation and cloud cover in a complex way, all of which are not known precisely. . Therefore, these heat loss data of the surface are much less precise than the temperature data of the sea surface and, in my opinion, they are not suitable for reconstructing the evolution of AMOC time.

That is supported by the fact that two different reanalysis data sets were used, which leads to quite different AMOC reconstructions. In addition, the evolution of the AMOC time they found differs from other reconstruction methods for the same period of time (see point 3 below).

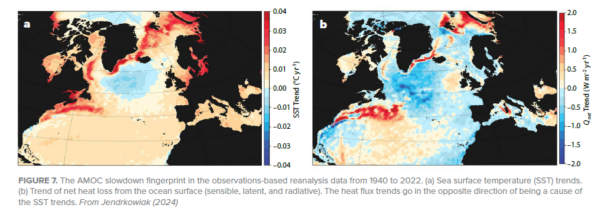

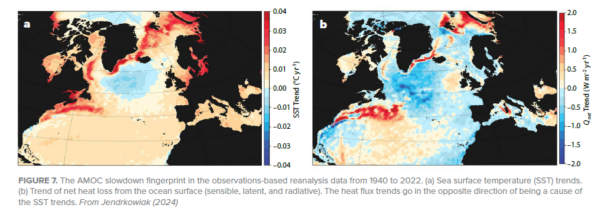

And there is another problem: we have previously analyzed the surface heat flow trend was 5, as shown here in my article in Oceanography 2024:

You will see in both figures (in temperature and surface heat flow) the MAOC deceleration ‘fingerprint’ that includes both the ‘cold spot’ and a heating along the US coast due to a change of current from the Gulf to the north , which is also an amoc weakening symptom. However, Terhaar et al. Integrate especially the North Atlantic north of 26 ° N so that the red area of augmented heat loss compensates largely by the blue area of decreased heat loss. So in your analysis these two things Cancelwhile in the established concept of the ‘digital footprint’ (see Zhang 2008: coherent fingerprint of the surface of the surface of the southern atlantic dump) These two things both reinforce The evidence of an AMOC weakening.

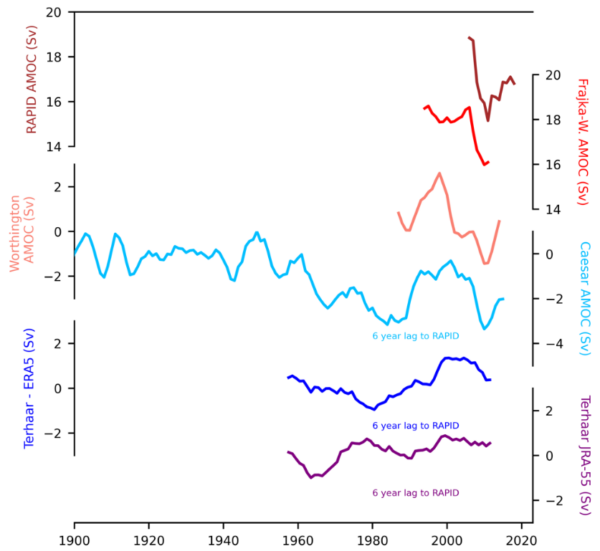

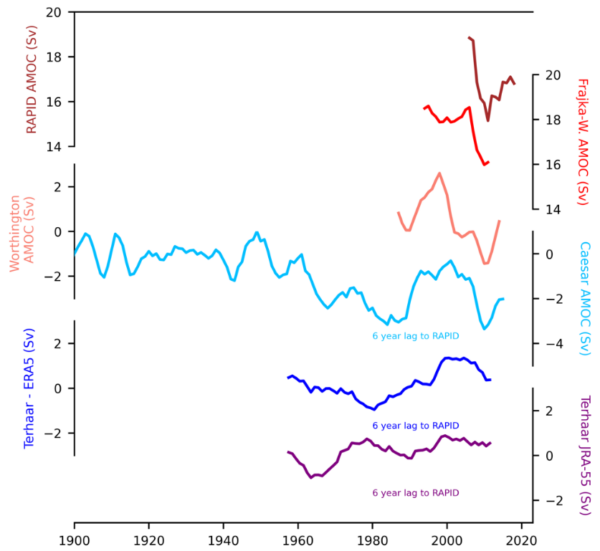

3. How do these new reconstructions compare with others?

This is how Terhaar reconstructions (two lower) are compared:

The reconstruction in the lower part using a reanalysis product of Japan does not resemble anything, while the blue that uses European reanalysis was at least has the minimum of the 1980s and early 2000s to the maximum in common with others data, although with a much smaller amplitude; It is much softer. Therefore, it also loses the strong decrease in AMOC 2004-2010 and the subsequent partial recovery observed in rapid measurements, as well as in César and Worthington reconstructions. A main reason for the lack of significant tendency in Terhaar’s reconstructions is the time interval they used; During the same time, César reconstruction also shows an even remote trend (the value P is only 0.5), so in this respect our reconstructions really agree during the period they overlap. The fact that ours shows a significant decrease in AMOC is due to the stable AMOC that we find during 1900-1960, which is stronger than in the following sixty years. Here our reconstruction method shows its advantage in that reliable and precise that there are temperature data of the sea surface until a long time.

Therefore, I do not believe that the new attempt to rebuild the AMOC is more reliable than the previous methods based on the patterns of temperature or salinity, in the changes of density in the region of ‘cold spot’ or in several data Paleoclimatic proxy, which have concluded that it exists. A weakening. But since we have no continuous current measurements in time far enough, some uncertainty about it. However, the new study does not change my evaluation of AMOC weakening in any way.

And everyone agrees that the AMOC will weaken in response to global warming in the future and that this raises a serious risk, if this weakening has already arisen from the natural variability in the limited observation data that we have or not. Hence the Open letter of 44 experts Presented in October at the Arctic Circle Assembly (see video of my Plenary presentation there), which says:

We, the insignified, are scientists who work in the field of climatic research and feel that it is urgent to call the attention of the Nordic Council of Ministers to the serious risk of an important change of oceanic circulation in the Atlantic. A series of scientific studies in recent years suggests that this risk has so far underestimated. Such change of oceanic circulation would have devastating and irreversible impacts, especially for Nordic countries, but also for other parts of the world.

Post script

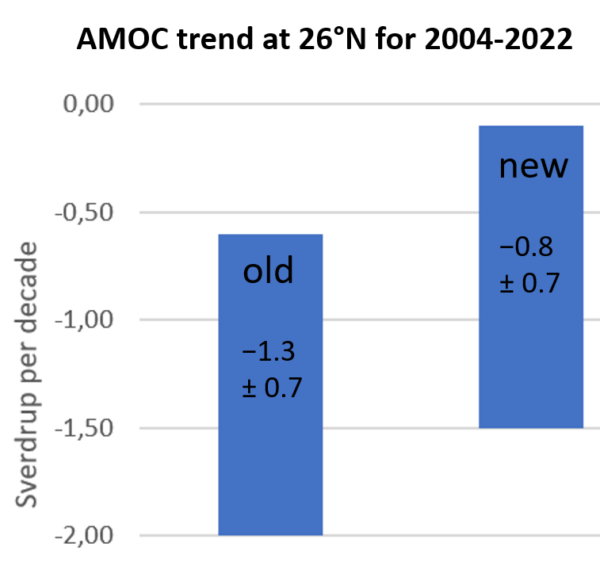

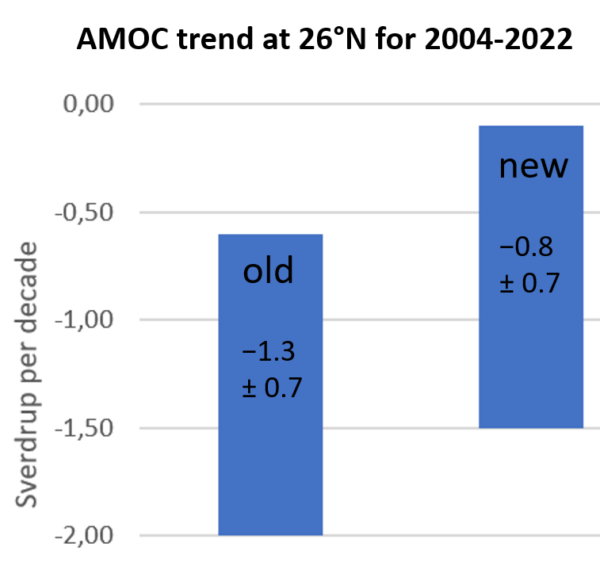

Since sometimes they ask me about that: last year a study of data from Volkov et al. He reviewed the deceleration trend of the flow of Florida and the AMOC. Contrary to the statements of ‘climatic skeptics’, it has no impact on our long -term estimate of ~ 3 sv deceleration since 1950, that is, -0.4 SV/decade (César et al. 2018). Both the original trend estimates and those reviewed for the data of the fast section (see figure) suggest that the recent weakening of AMOC since 2004 is more pronounced than the long -term trend we estimate.

#amoc #slowing #stable #slowing