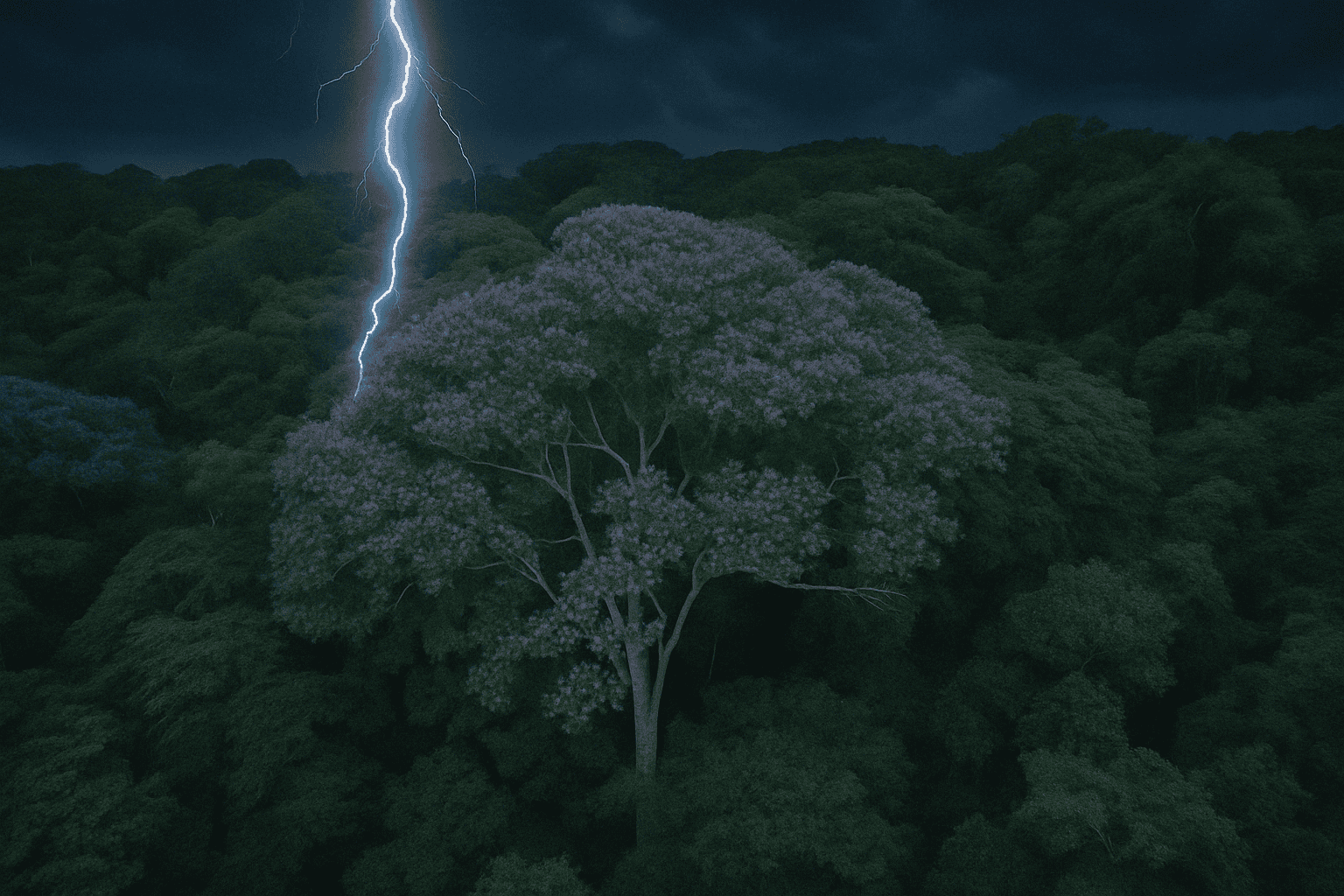

In a tropical jungle full of competition, a tree has discovered how to turn the catastrophe into an advantage.

In the dense jungle of lowlands of Panama, a tropical species called Dipteryx oleifera– Known locally as a almond or the Tonka bean tree, it has evolved a surprising relationship with lightning. When the screws stand out for heaven and hit the imposing tree, not just survive. It blooms.

The selective blow of nature

Lightning has long been considered an indiscriminate murderer in tropical forests. Every year, scientists estimate, hits trees in the tropics millions of times. Those screws generally kill the trees they hit, but also open gaps in the canopy, making space for a new life. But the last study, published in New Phytologist He says things are not so simple.

Directed by the Tropical Ecologist Evan Gora of the Cary Institute for Ecosystems Studies, the study shows that Dipteryx oleifera It can be evolving with lightning, not simply survive, but take advantage of it.

“We began to do this job 10 years ago, and it became really evident that Lightning kills many trees, especially many very large trees,” Gora told Live science. “But Dipteryx oleifera constantly showed no harm. “

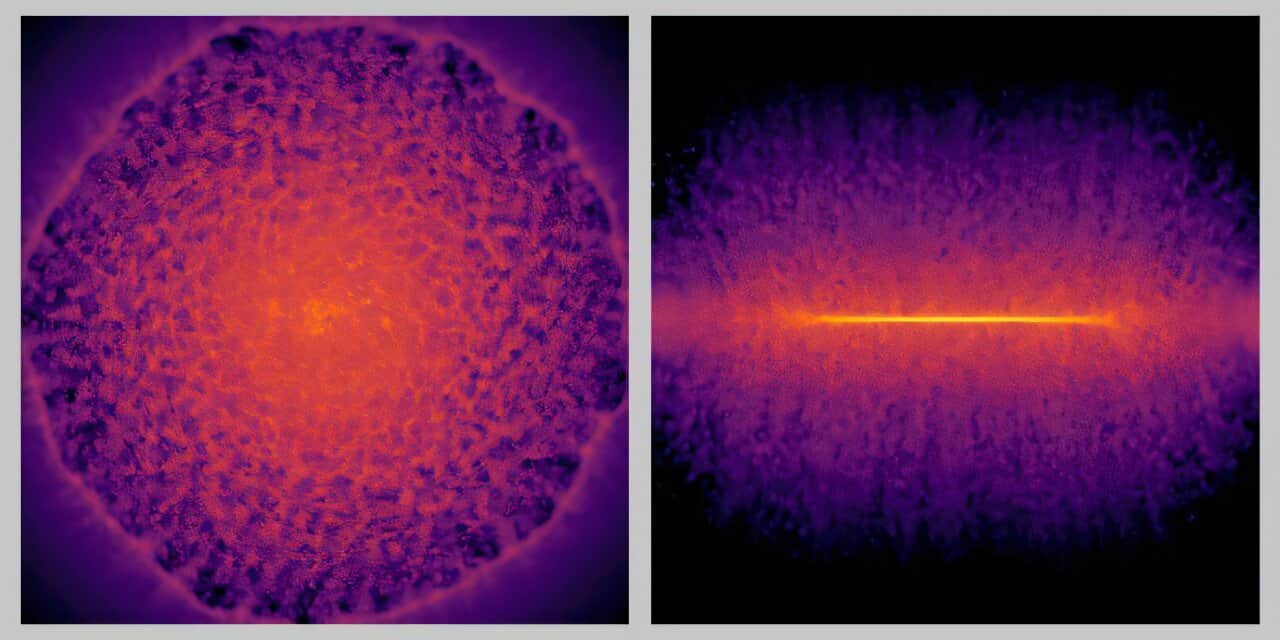

This was no accident. Between 2014 and 2019, Gora’s team tracked 93 trees that had been beaten by lightning using a network of custom sensors and high -resolution images. Of them, nine were D. Oleifera. Each survived. Its competitors were not so lucky.

Most of the neighboring trees did not succeed. On average, lightning near a D. Oleifera He killed nine surrounding trees and an infestation of reduced parasitic vines, particularly lianas, at 78%. These vines normally adhere to the canopy, stealing the host tree of sunlight. After the strike, the almond was alone, bathed in light, without rising for parasites and with less competition for nutrients. Lightning solved all the problems of the tree in a single blow.

A thorny advantage

This is where it becomes even more interesting. The study also suggests that D. Oleifera Not only tolerates the rays. It can attract it.

With a height of up to 165 feet and crowned with a wide canopy, D. Oleifera It has 68% more likely to be beaten than other trees. The researchers suspect that this is not accidental. Its height and crown shape make it a natural grill. The team discovered that throughout its useful life of 300 years, a mature tree is beaten about five times.

“Any tree that is essentially electrocuted,” Gora told Science.

While nearby species suffer, D. Oleifera It seems to gain a massive evolutionary advantage. The study estimated that ray trees could see an increase of 14 times in seed production during their life. That is a massive reward in evolutionary terms.

The mechanism behind this resilience is not yet clear. An idea is that the wood of the tree performs electricity efficiently, which allows the current to travel through the trunk without generating harmful heat. Another possibility is that its architecture redirects the surrounding air or neighboring trees.

A new role for an old strength

This research is part of a growing reevaluation of the Lightning ecological role. For years, forest scientists understood that rays were one of the many forces that shape ecosystems. But few realized that it could shape the evolutionary routes of specific species.

The implications are surprising. If the ray influences which trees live and die, could play a role in the configuration of entire forest communities. That becomes more urgent in a world with changing climatic patterns.

Rays are expected to become more frequent and intense as the atmosphere is heated. A 2014 study projected a 12% increase in the ray frequency for each 1 ° C increase in the global temperature. That could make the selective pressure even more powerful.

I could also help explain why certain trees, such as D. OleiferaIt evolved such unusual characteristics in the first place. And in the middle of that story, at the extreme receiver of nature, there is a tree that could be playing the long game.

#tree #survives #rays #kill #rivals