February 6, 2025

5 Read minimal

Why the ‘fork on the road’ of Elon Musk is really a dead end

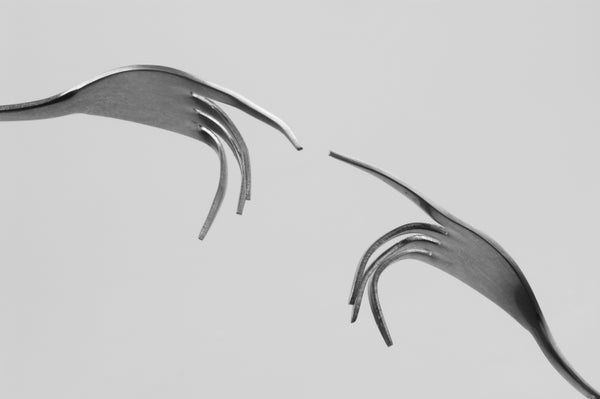

Elon Musk’s Fork on the road It is not just a sculpture: it is a monument to the obsession of the technological world with civilizational survival, which has its roots in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence

Unlike the utensils of the Sistine Chapel in this stock photo, Elon Musk’s Fork on the road It seems more about reading history deliberately than obtaining any type of divine inspiration.

On December 7, 2024, Elon Musk shared an image of works of art that he had commissioned for Tesla HQ entitled A fork on the road. A colossal piece planted at the intersection of three paths, is not subtle, is literally a holder along the way.

The sculpture returned to the headlines less than two months later, when the Trump administration sent an email with the “bifurcation on the road” issue, echoing a previous email had sent to Twitter employees with the same title , both urging massive resignation. News reports suggest That musk and its government efficiency department (Dux) were behind the resurgence of the phrase.

The theme of “bifurcation on the way” suggests A trend in the technology industry: a concern for existential threats, that finds resonance in the ideas of the cold war. In this simplistic binary, the future of humanity can only follow two divergent paths: one notionally that leads to an almost unlimited prosperity on earth and beyond, the other is no more in addition to the collapse of our global civilization and, ultimately instance, human extinction. The defenders of this survival mentality see it as a justification for particular programs of technological climbing at any cost, framing the future as a desperate career against catastrophe instead of a space for multiple prosperous possibilities.

About support for scientific journalism

If you are enjoying this article, consider support our journalism awarded with subscription. When buying a subscription, it is helping to guarantee the future of shocking stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape our world today.

This existential anxiety bubbled the surface in its position on December 7, when Musk subtitled the photo of the sculpture with a cryptic statement: “I had to ensure that civilization took the path with more likely to pass the great Fermi filters” .

Musk’s reference to “Fermi great filters” combines two different but related ideas that have become popular in technological circles: the Fermi paradox and the concept of existential filters. The paradox originated in 1950, during a conversation at lunch time in the National Laboratory of Los Alamos. Enrico Fermi, a leading nuclear physicist who worked on the Manhattan project, and his colleagues were discussing UFOs, perhaps caused by the madness of the 1947 flying album that had shaken the country only a few years earlier. Given the large number of potentially habitable and innumerable planets plausible methods for interstellar communication or trips, they asked why humans had not yet found evidence of alien civilizations. Fermi summarized the dilemma in a single question: “Where are they all?“

The apocryphal story has become a popular mental experiment. A common explanation for the apparent absence of extraterrestrial neighbors is what Economist Robin Hanson described the “great filter”—The idea that there is an important obstacle that prevents civilizations from reaching a stage in which they have the ability to send messages or tripled trips to other stellar systems. The great filter can be behind us, which means that life on Earth has already exceeded the chances of overcoming a catastrophe, allowing our civilization to develop. Or otherwise, we could face some challenge that is difficult to survive. Although the term itself is quite new, it is based on the concepts of the Cold War, particularly those linked to the Kardashev scale, a framework developed in the 1960s that speculated on how extraterrestrial civilizations could progress.

The Kardashev scale It has become a key influence on some technologists. Proposed in 1964 by the Soviet astronomer Nikolai Kardashev, the scale classifies extraterrestrial civilizations according to their energy use: type I civilizations take advantage of all the energy available on their native planet; Type II civilizations capture the total energy production of its star; and type III civilizations command energy on the scale of their entire galaxy. Musk has cited the Kardashev scale in X for a dozen times in the last year, often framed the progress of humanity in terms of ascending it (once he wrote: “Any civilization that respects itself should at least at least should Reach Kardashev Type II. “) Originally a mental experiment, the scale now is often treated as a literal roadmap, which is a desirable, even inevitable trajectory, towards greater energy consumption and interstellar expansion.

The Cold War, which gave us both Fermi’s paradox and the Kardashev scale, was defined by existential anxiety. Nuclear weapons marked the possibility of the rapid self -destruction of humanity, and The scientists were very aware of his qualifying role in the possible disappearance of our species. This fear deeply influenced Early Seti scientistsshaping their ideas about the civilizations they expected to find in the galaxy. Often, their imagined civilizations reflected their own anxieties and aspirations.

The Kardashev scale approach in energy consumption such as the main metric of the advance reflects a clear worldview of the twentieth century, a form for multiple overlapping technological revolutions. Kardashev developed its scale as part of a broader exploration of how extraterrestrial supercivilizations could be: vivilizations not very different from what in some evaluations the Soviet Union aspired to become, with its spatial ambitions, imperial scope and technological power. The scale was designed as a tool to help Seti scientists imagine the types of artificial signals that such civilizations could produce. Kardashev was not an oracle or a prophet; He was a 30 -year -old astronomer who lived behind the iron curtain, dealing with the possibilities of a future that, for him, seemed formed by an intoxicating mixture of hope and fear.

Existential anxiety has now also become generalized in the technological world. It drives technology billionaires to invest in space programs, Lawyer for pronatalist policies to counteract a collapse of the feared populationand promotes multiplaneary settlement as an escape from climate change and other earthly problems. But while the concerns about the possible catastrophe are not exempt from merit (although we have left the cold war behind us, there is no shortage of existential dilemmas that face our civilization), there is something reductive in framing the future in such or nothing terms.

On the other hand, we must be deeply skeptical of the narratives that present the progression of civilization as a unidirectional path, a unique path that inevitably leads to a predefined notion of “progress”, with all the deviations that results in fatality. Is humanity really on the edge of the unprecedented fooming or imminent doom, or is this other iteration of an ancient tendency to see the present moment as in a unique way? The Kardashev scale and the great filter are fascinating ideas that drive us to consider the trajectory of civilizations, how they could take advantage of energy, navigate existential risks and potentially reach beyond their origin planets. But when they deal with fixed and predictive frameworks, we run the risk of reducing the complexity of future humans and extraterrestrials to a crude cartoon of progress.

But even if you accept a prescription interpretation of these ideas of the cold war, why assume that Musk and other technological prints have the key to becoming a type II civilization, or avoiding the great filter? If we take “fork on the way” to the letter, what justifies the belief that they are the ones who have the solution? Could not be part of the problem, accelerating the same conditions (oligarchic control, systemic inequality and environmental degradation) that could lead to an existential catastrophe? The irony is that his speculative spirit, when he turns on himself, reveals his own contradictions: a worldview that claims to safeguard the future of humanity could easily be strengthening the power structures that threaten him.

That the acrytic hug of the theories of the cold war is now justifying aggressive changes to the United States government and its workforce underlines its generalized influence, but also highlights its limitations. By frameting humanity’s challenges as simple engineering problems instead of systemic complexes, technologists position themselves as decisive architects of our future, creating great visions that leave aside the most disorderly and necessary work of social, political and collaborative changes.

The real bifurcation on the road is not between survival and extinction, but between repeating the patterns of the past and embrace a richer vision of progress, one that recognizes multiple paths and possibilities, and rejects the notion that our destiny must rest in the hands of technological billionaires.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the opinions expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.

#Fork #Road #Elon #Musk #dead