September 30, 2025

4 minimum reading

Rock art discovery reveals unknown Arab nomads from 12,000 years ago

Camels in ancient Arabia may have guided hunter-gatherers through deserts once considered uninhabitable

Camel carvings indicate paths to ancient oases at four remote desert sites.

Sahout Archeology and Rock Art Project

A newly discovered work of prehistoric art suggests how a pioneering sect of desert nomads, unknown to history until now, carved out an existence for themselves around 12,000 years ago in the harsh environment of northern Arabia.

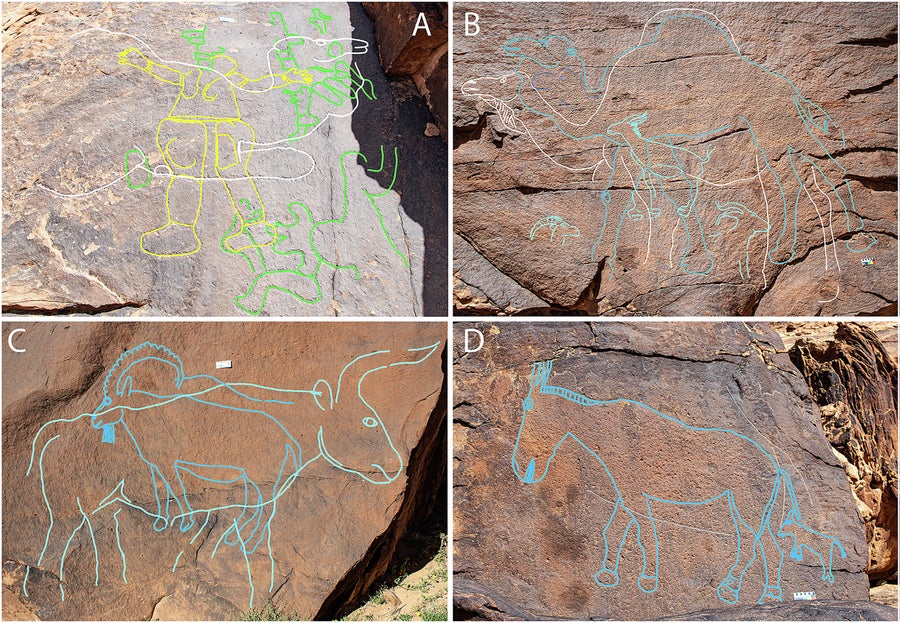

At four remote sites near Saudi Arabia’s Nefud Desert, researchers are puzzling over more than 130 life-size animal images adorned on rock outcrops. Wild camels dominate the carvings: 90 of them run alongside other ancient beasts that once roamed the arid landscape. The wide antlers of the sure-footed ibex stand out. Ancient horse-like equids are shown with their young. A depiction of an aurochs, a burly, extinct bovine that required a lot of water, suggests wetter environments, but only a little wetter, say the archaeologists who discovered the artwork. Their sediment analysis reveals seasonal lakes at two of the sites: ephemeral watering holes that were possibly shared by hunter-gatherers and other animals. And the camel engravings give clues to the circumstances of the encounters. At that time, livestock had not yet been domesticated and herds of camels still lived in the wild. In fact, the camel adapted to the desert stands out as the favorite subject of ancient artists.

“I wonder if these humans looked at the camels and thought, ‘Wow, these guys really know how to get by when there’s no water,’” says Maria Guagnin of the Max Planck Institute for Geoanthropology in Jena, Germany. She was co-author an article about the discovery of artwhich was published today in Nature Communications.

About supporting scientific journalism

If you are enjoying this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription, you help ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape our world today.

There was so little water in northern Arabia at the end of the last ice age, about 11,700 years ago, that most experts had assumed it was uninhabitable at the time, Guagnin says. But now the artifacts that researchers in the new study unearthed, such as stone tools, arrowheads and hearths, some of which were found immediately adjacent to the carvings, show that a highly mobile population thrived there for more than 2,000 years, he says.

Composite drone photography showing a rock art panel at Jebel Misma, featuring 19 camels and three life-size equids. The earlier representations are drawn in white and the later ones in blue. On the left is a scaled human outline.

Sahout Archeology and Rock Art Project

In rock art, all camels appear like these animals in winter: with shaggy coats and necks swollen from mating vocalizations. Winter was the rainy season in the region, meaning camels and their human admirers likely congregated around water-filled lake beds, the researchers say. These connections raise the possibility that people were following camels across the desert on their winter migrations, says archaeologist and study co-author Ceri Shipton, who was excavating the site, known as Jebel Misma, when her team spotted a spectacular caravan of camel sculptures on May 14, 2023.

That morning, one of Shipton’s assistants, Saleh Idris, looked up and exclaimed, “Jamal, jamal!” (camel in Arabic). Shipton looked up, too, and, he recalls, “suddenly the sun came out round enough that I could see them all over the cliff, and I said, ‘My God, it’s covered in them.’”

“It’s a bit of indiana jones,” Guagnin says, “because you can only see it for about an hour and a half in the morning, when the sun comes up, goes up over the mountain and hits it just right. And then the sun rises a little further, all the contrast is lost and it is invisible until the next morning.”

Rock art panels at Jebel Arnaan. The rubbings highlight the layers of engravings, showing phase 1 in green, phase 2 in yellow, phase 3 in white, and phase 4 in shades of blue.

These carvings are located just above a ledge barely wide enough to gain a foothold, on a sheer rock wall more than 100 feet high. “That means they had the surface of the rock directly in front of their noses, and at no point could they see the whole animal. They must have had an engraving tool and basically hammered it…, going from one side to the other, and somehow created this whole animal along the surface of the rock,” Guagnin says.

Many of the camel carvings are layered on top of each other and vary slightly in style over time, from realistic to more cartoonish and abstract, a progression, Guagnin says, that could mean the artists were developing a shared concept of the camel. The continuous effort to update the sizes establishes their use over long periods. The researchers propose that they were intended to guide thirsty hunter-gatherers to water sources that were often hidden behind rocks and sandstone formations and to mark access rights.

Guagnin herself was guided by camel art at Jebel Aarnaan, another site also described in the article. “If you go behind the rock, you realize that it opens up into a small valley that leads to a mountain,” he says. “And the whole mountain valley is lined with rock art. And it turns out that it’s actually a shortcut to the other side where there’s a lake, so it connects you to the nearest water source without having to go the long way.” There and at Jebel Misma, the team found tools for hammering stones left by artists in sediment layers dating back 12,000 years. That makes the carvings several millennia older than similar art found elsewhere in Arabia, says Guillaume Charloux, an archaeologist at the French National Center for Scientific Research, who was not involved in the study. Their age “profoundly transforms… our understanding of prehistoric art in the Arabian Peninsula” because it means the camel creations coincided “with the heyday of rock art in Western Europe,” he says.

It’s time to defend science

If you liked this article, I would like to ask for your support. American scientist has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in those two centuries of history.

I have been a American scientist subscriber since I was 12 and it helped shape the way I see the world. Science-Am It always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of wonder at our vast and beautiful universe. I hope it does it for you too.

If you subscribe to American scientistyou help ensure our coverage focuses on meaningful research and discoveries; that we have the resources to report on decisions that threaten laboratories across the United States; and that we support both budding and practicing scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unnoticed.

In return, you receive essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, Newsletters you can’t miss, videos you must see, challenging games and the best writing and reports from the scientific world. You can even give someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you will support us in that mission.

#Rock #art #discovery #reveals #unknown #Arab #nomads #years