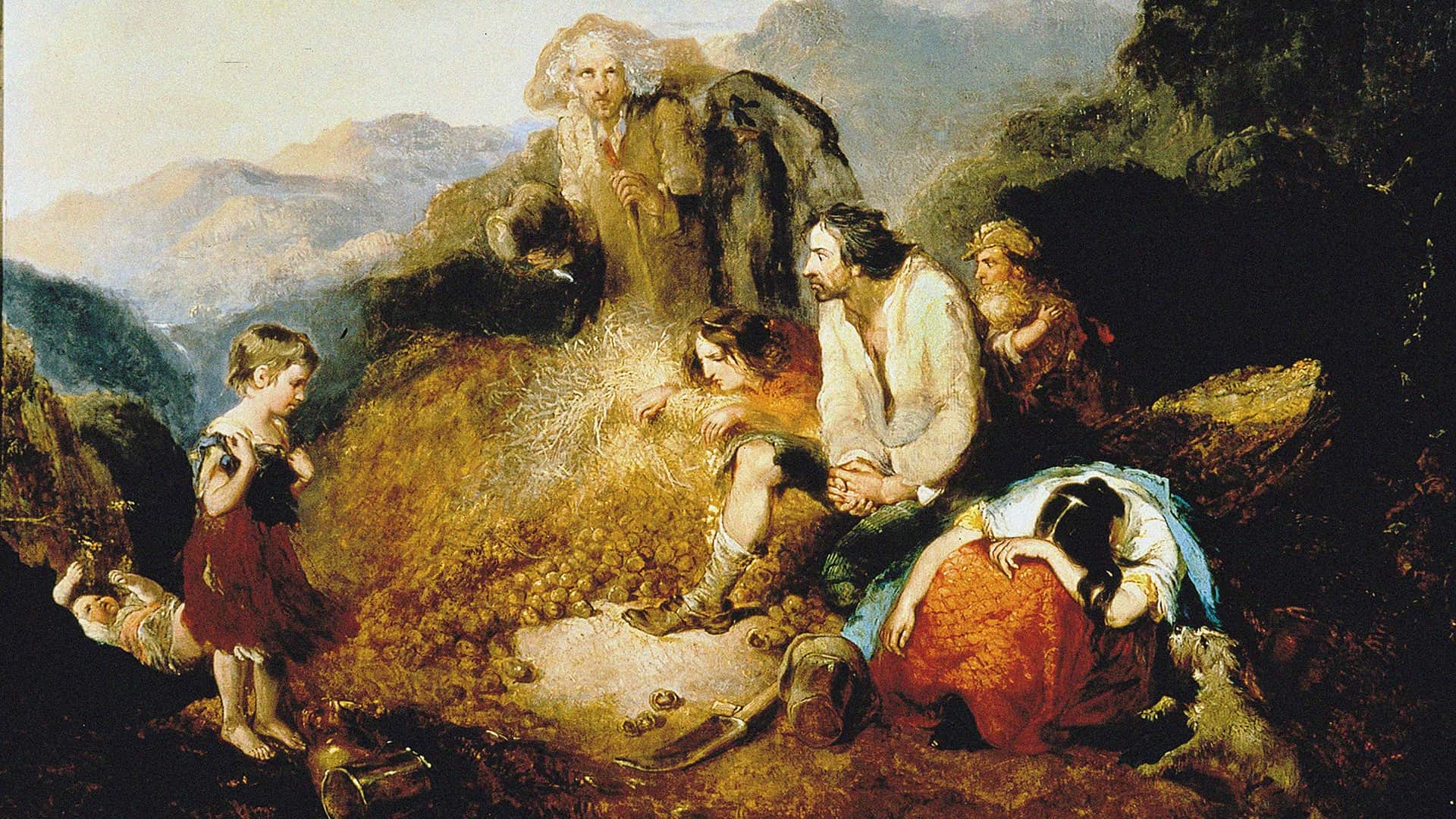

In the mid -nineteenth century, a microscopic invader spread through Ireland, leaving a trace of devastation in its path. Pope blight, caused by fungus -type pathogen Phytophthora InfestansHe unleashed a famine that killed more than one million people and forced millions to flee. For more than a century, scientists have discussed where this deadly organism emerged for the first time. Were the resistant Andes, where the potatoes were domesticated for the first time? Or were the highlands of Mexico, a region full of similar pathogens?

Now, a team of researchers claims to have solved the question. In one of its largest genetic studies, they have tracked the origins of the potato blight to the Andes. The findings not only establish one of the darker debates of long data, but also reveal a complex network of evolution, migration and hybridization that shapes the history of one of the most infamous plant diseases in the world.

The journey of a pathogen

Even today, Phytophthora Infestans It continues to wreak havoc in potato and tomato crops worldwide, causing billions of dollars in losses every year. Learning where it originates could help scientists predict and fight future outbreaks.

The debate about his birthplace has been fierce. Some researchers defended a Mexican origin, pointing out the sexual reproduction of the pathogen in the region. Others, citing genetic evidence, proposed an Andean origin. The new study, led by Allison Coomber and Jean Ristain of the State University of North Carolina, provides a large amount of genomic data to the table.

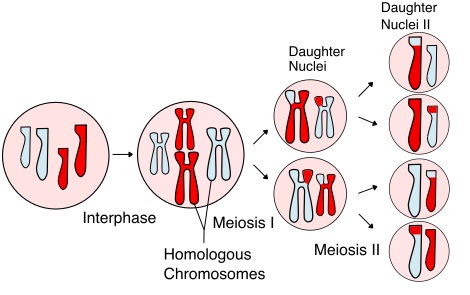

The team analyzed complete genome sequences of P. infestans and six closely related species, including P. Andina and P. Betaceithat are found in South America, and P. Mirabilis and P. ipomoeaeNative of Mexico. Also included historical samples of P. infestans Collected during the Irish potato famine.

The results were clear. The Mexican species, P. Mirabilis and P. ipomoeaeThey formed different genetic groups, separated from P. infestans. In contrast, P. infestans I was closely intertwined with the Andean species P. Andina and P. Betacei. These last three species form a complex with indistinct limits. They are more like brothers than distant cousins.

“This is how science works” saying Jean Ristino, co -author of the study and professor at the State University of North Carolina. “There is a hypothesis, people question it, prove it, present data. But over time, the evidence is really weighted in favor of the Andes, because DNA does not lie. Genetics shows ancestry in that region. “

Historical records also point to the Andes. “In 1845, when this blight arrived in Europe and the United States, people were immediately trying to find out where Ristain added during an interview with The guardian. “There were reports that the disease had happened and was known among the indigenous Andean Indians who cultivated potatoes.”

The Andean melting

According to genetic analysis, the common ancestor of P. infestans And their Andean relatives diverged from Mexican species about 5,000 years ago. Over time, P. infestans It extended from the Andes to other parts of the world, including Mexico and Europe, thanks to the increase in trade and globalization abroad.

The study also revealed surprising levels of gene flow between P. infestans and his Andean relatives. Migration rates between these species were much higher than those involving the Mexican species. This suggests that the Andean region is not just the birthplace of P. infestans but also an access point for continuous evolution.

One of the most intriguing findings was the blurred line between P. infestans, P. Andinaand P. Betacei. These Andean species are so closely related that they often hybrid, creating new genetic combinations. It is like a melting with all these genes of exchange of microbial species, which could lead to new strains with different virulence features, some of which could overcome the resistance of plants.

Understanding where the devastating blight of potatoes originated has important practical implications to control this disease, which remains a global threat.

Potato Blight continues to wreak havoc around the world. In Europe, strains resistant to fungicides have emerged, which forces farmers to seek new chemicals and methods. The new gene methods and edition of genes could offer a long -term solution.

“When you know the center of origin of a pathogen, that’s where you will find resistance,” Ristain said. “In the long run, the way to control this disease is through host resistance. This work shows that the approach to reproduction efforts must occur in the Andes. ”

As the world dealt with the challenges of food security and climate change, studies like this are more important than ever.

The findings appeared in the magazine Plos one.

#Scientists #finally #solve #mystery #origins #Irish #potato #blight #Wine #Andes