In about a decade, total water demand will exceed available supply globally. This will be a difficult problem for decision-makers and regulators, what Sir James Bevan, chief executive of Environment Agency England, calls “the jaws of death”. London, along with many other major cities around the world, will be severely affected. It will not be enough to put emphasis on reducing consumer demand; This is a lesson we learned from the major drought that hit Cape Town in 2018. New sources of supply will need to be found alongside demand management solutions. Among supply-side options, inter-basin transfer (IBT) schemes have received less attention from both academia and industry. The construction of an IBT requires considerable investments and can also have negative impacts on the export basin that must be studied.

In this regard, a team of UK researchers (HR Wallingford, the University of Newcastle and the Tyndall Center for Climate Change Research) provided a framework to be implemented during the planning and design stage of an IBT. This framework can be used for feasibility studies regardless of the type, location, design and means of the IBT.

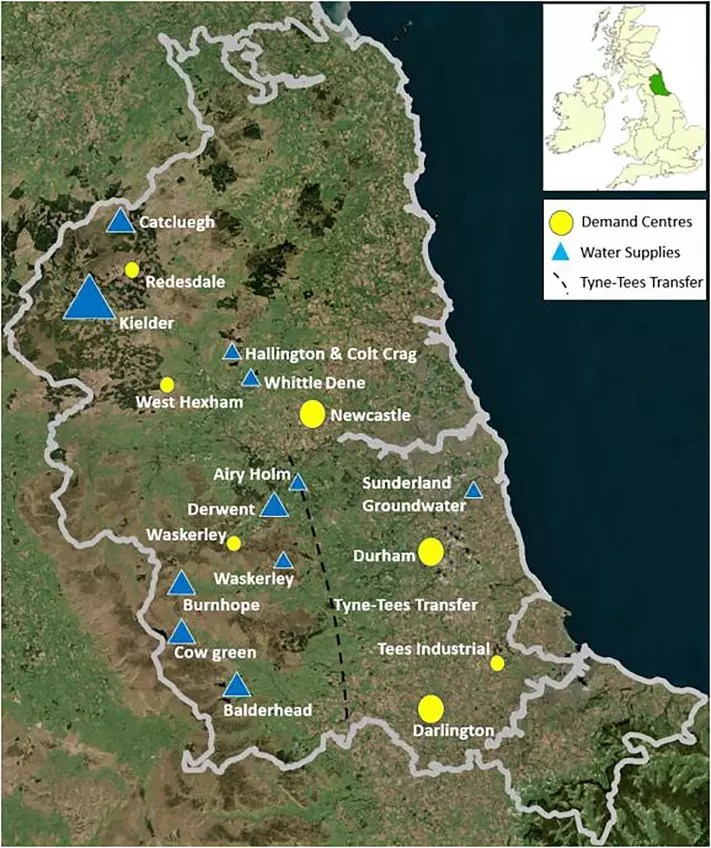

They used this framework to assess the initial climate impact of a hypothetical IBT scheme that will deliver water from Keilder Reservoir in the northeast of England to London in the southeast. They stated: “This choice is based on the fact that Kielder is the largest reservoir in the UK and is located in one of the least water stressed regions.”

The proposed framework estimates the spatial and temporal distribution of water flow and storage across the catchment area using the climate projection for precipitation and potential evapotranspiration (UK Climate Projection 2018; UKCP18). This data is then modeled in a rainfall-runoff model to calculate future inflow time series to determine stream storage capacity and temperature. The proposed framework was evaluated against 100 future climate scenarios generated from the driest member of the UK Met Office UKCP18 for the donor catchment.

Dr. Khadem and his colleagues assessed the negative ecological and hydrological impacts of the hypothetical. The impact of this hypothetical IBT was evaluated under three transfer scenarios. In the “NoTransfer” scenario, there was no demand for water from the London IBT and water from Keilder Reservoir was used within its resource zone. In the “AllYearTransfer” scenario, there was a continuous demand for water from the London IBT during each year. In the “WinterTransfer” scenario, the London IBT is operational only in the winter months (i.e. October to March) while covering London’s annual water deficit.

The hydrological impact was evaluated by evaluating whether the IBT causes drought in the exporting basin. The hydrological risk of possible droughts in the Kielder basin was higher in the “AllYearTransfer” scenario. In this case, this IBT will have difficulty meeting demand and will cause a drought in the Kielder water resources area. However, the transfer under ‘WinterTransfer’ shows that there will be no adverse hydrological impact as the donor basin is experiencing high flows. Ecological impact was assessed by assessing whether the change in flow and storage volume will alter stream temperature and destroy freshwater habitat. In all three scenarios a low river temperature was predicted without any negative ecological impact on the Kielder catchment.

The research team’s findings have successfully demonstrated that an ambitious north-south IBT can draw water from the Keilder reservoir to cover London’s shortfall by transferring large volumes of water in the winter months, even under the driest UKCP18 climate projection. This is not the only option available to decision makers, but this study shows that it is a viable and viable option to consider, and perhaps a starting point for further analysis. “The current water resources management plan comprises a portfolio of leakage reduction, demand reduction, new groundwater and reuse schemes, and regional transfers. However, if population growth is higher, demand reduction does not produce the necessary benefits, or if the higher standard of drought resistance required by the National Infrastructure Commission is imposed, then a long-distance IBT may be essential to sustain London’s water supply,” said lead author Dr. Khadem.

Magazine reference and image credits:

Khadem, Majed, Richard J. Dawson, and Claire L. Walsh. “The feasibility of inter-basin water transfers to manage climate risk in England”. Climate Risk Management (2021): 100322. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2021.100322

#Transfer #schemes #basins #big #elephant #room