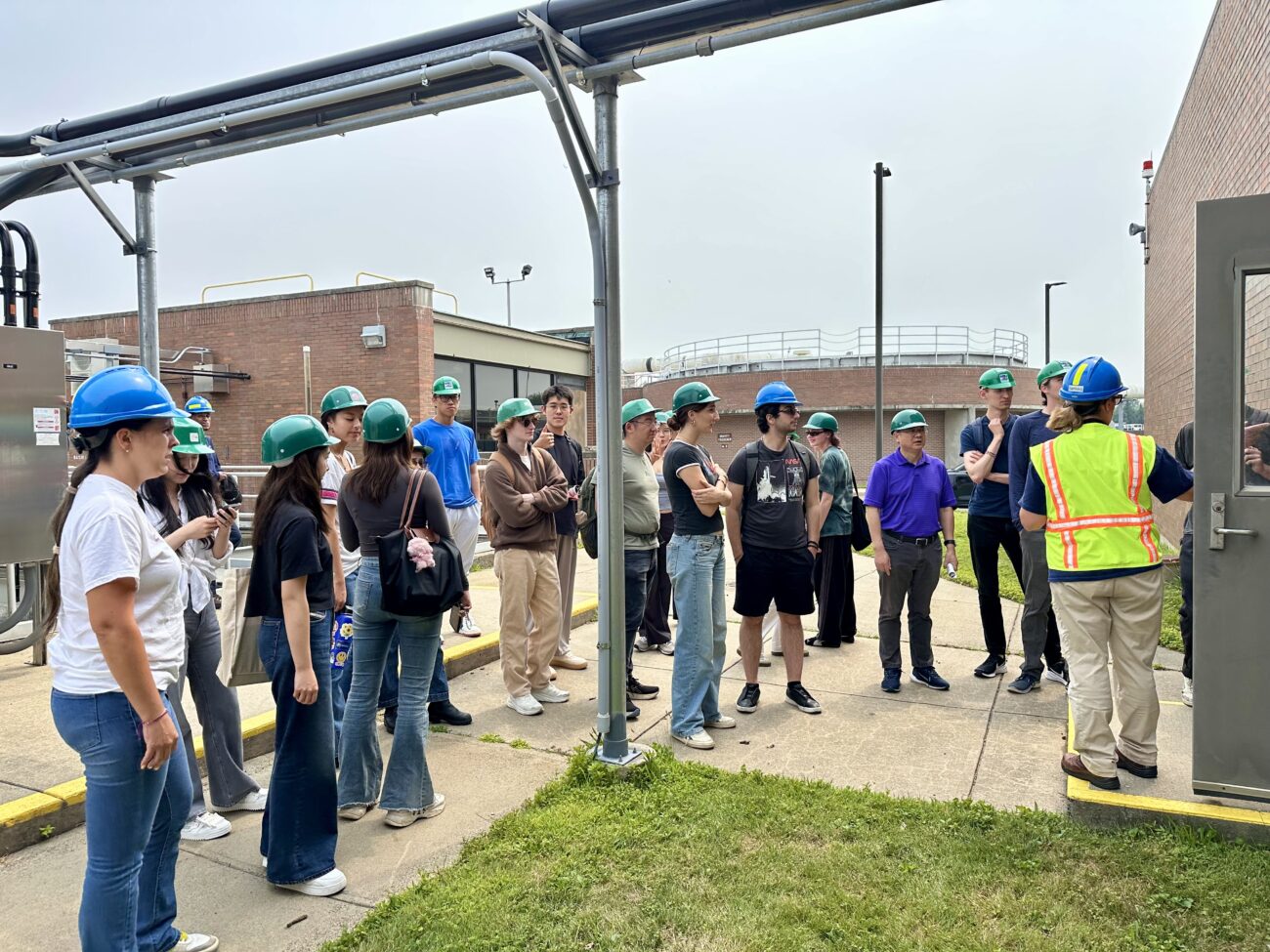

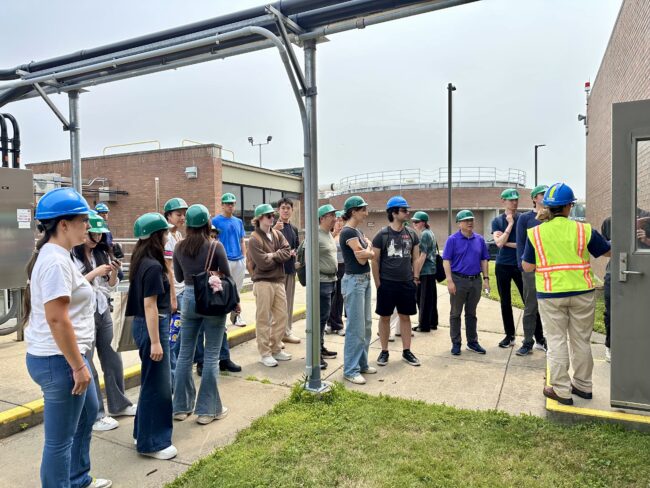

At the end of the summer semester, Columbia University students AMP in environmental science and policy The program visited Stamford, the Connecticut Water Pollution Control Authority and its municipal recycling operations. At first glance, these facilities represent the kind of critical behind-the-scenes infrastructure that most of us take for granted: wastewater treatment plants that protect public health and ecosystems, and recycling/composting efforts that aim to reduce what ends up in landfills. However, as future policymakers, water and waste managers and advocates, we are left with as many questions as answers.

Wastewater: essential but fragile

One of Stamford’s notable achievements is its separate sewer and stormwater system, which reduces the risk of flooding and helps maintain cleaner waterways. The facility also derives some of its energy from solar energy, a step toward sustainability.

As student Brendan Chapko noted during the visit, the Stamford team opted to move away from chlorine and embrace UV disinfection.

“They decided to switch from chlorine to UV, making the water leaving the plant even cleaner than necessary, protecting the rest of the equipment and helping to ensure that what flows into Long Island Sound is as safe as possible,” he explained.

Advanced Nitrogen Removal: Innovation with Impact

A highlight of the Stamford plant is its advanced nitrogen removal system, which not only improves Long Island Sound water quality but also participates in the Connecticut project. nitrogen credit exchange program. This state initiative allows municipalities to buy and sell nitrogen credits, rewarding plants that reduce nitrogen discharges below their allocation.

In 2018, Stamford earned a performance score of 633 nitrogen reduction credits in the Connecticut Nitrogen Credit Exchange Program. With the value of the state credit set at $11.02 that year, Stamford received a total payment of $2.5 million, funds that can be reinvested in treatment improvements, system improvements or community initiatives.

It’s worth asking: Could nitrogen credit trading models elsewhere be scaled up or adapted as a way to incentivize environmental performance and create sustainable financing for infrastructure?

Recycling and composting: aspirations and contradictions

Stamford stands out as one of the few cities in Connecticut with a functional citywide recycling and composting program, often cited as a local leader in this area. The city offers public food waste drop-off sites, along with seasonal leaf and Christmas tree composting initiatives, initiatives that reflect an encouraging commitment to waste diversion.

However, even leadership comes with challenges. Much of Stamford’s trash still travels hundreds of miles to Pennsylvania landfills, as recycling often costs more than disposal. This economic imbalance undermines the long-term viability of circular economy solutions. The city once explored a waste-to-energy project, but it did not move forward. While these facilities can reduce reliance on landfills, they are not truly circular, as they destroy materials rather than keeping them in productive use.

The composting program also has clear limitations. A state law requires composting in schools, but it applies to only five of Connecticut’s largest schools. Food scraps at the Stamford facility are dehydrated to reduce volume and rodent risk, but concerns remain about microplastic contamination, arising not only from the mixed waste but also from the composting process and temperature conditions used.

There also seemed to be less emphasis on prevention, such as reducing food waste before it is created. In a country where household food waste is particularly high, prevention could be the most transformative and cost-effective strategy. Shouldn’t prevention be at the core of any sustainable food waste program?

There are also open questions here: For example, should Connecticut invest in regionalized composting and waste solutions to achieve economies of scale? How can municipalities more actively involve the private sector, which generates a significant amount of waste and could help drive innovation? And perhaps most urgently: how can we make prevention, and not just management, the centerpiece of future strategies?

Tradeoffs and transitions

The facility’s efforts to adopt renewable energy and ban plastic bags are positive steps. But here we must be precise: the main value of banning plastic bags in this context is operational, as it prevents bags from clogging wastewater systems and limits their decomposition into microplastics in compost. However, wipes and other single-use products continue to put a strain on the system, and will continue to do so until the root of the problem is directly addressed: awareness and education.

These questions bring to light a more uncomfortable truth: in sustainability, complexity often means that we cannot “solve” problems directly. Sometimes we can only improve things gradually. But this should not be a cause for complacency. Instead, it challenges us to co-create solutions that go beyond technical solutions, combining policies, business models and everyday practices to make those incremental steps add up to deeper change.

people in the center

If one theme stood out it was the role of people and communities, all residents, regardless of their origin or status. These systems exist to serve the public, funded by tax dollars. However, without collective participation, even the most advanced infrastructure cannot fully deliver on its promise. Everyday decisions about what we buy, throw away, recycle or dispose of can make or break the system.

But households cannot take on this responsibility alone. Private sector involvement will also be critical: companies generate large volumes of waste, shape consumer choices, and often lead innovation. His stronger presence in Stamford’s strategies could make a significant difference.

Beyond the classroom

For us as students, this visit was more than an excursion. It was a hands-on opportunity to question practices, weigh trade-offs, and imagine alternatives. As future policymakers, administrators, funders, entrepreneurs or community advocates, our responsibility is not just to admire existing systems, but to question their adequacy and dream of better ones.

Today’s pipes and containers reflect collective choices, trade-offs, and values. Are we prepared to drive those options beyond incremental solutions toward truly resilient, fair and circular systems?

Expressions of gratitude

We extend our thanks to Maya Lugo, deputy director of the MPA-Environmental Science and Policy program and research professor at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. Beizhan Yan for organizing this visit as part of the Hydrology course. Special thanks to Dan Colleluori, director of recycling and sanitation; Marylee Santoro, WPCA Stamford Laboratory; and the staff at the Stamford facility for their hospitality and valuable knowledge. We also thank the students for their active participation, which enriched the discussion, and Sara Haris, MPA-ESP program liaison for her contributions to this post.

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Columbia Climate School, the Earth Institute, or Columbia University.

#visit #Stamford #wastewater #recycling #facilities #reveals #elections #State #Planet