Within a laboratory in South Korea, an iris arc shine caught the attention of a graduated student. This brightness is the product of something extraordinary: diamonds, born not of the crushing pressures in the depths of the earth, but of a group of liquid metal under atmospheric pressure. These new synthetic diamonds could change the way we make one of the hardest and most coveted materials in the world.

Breaking the diamond mold

Natural diamonds are forged in the upper mantle of the earth, where temperatures rise to 900–1400 ° C and pressures reach 5–6 gigapascal, thousands of times larger than the pressure at sea level. Since the 1950s, scientists have replicated these conditions in the laboratory using high pressure and high temperature (HPHT) methods to create synthetic diamonds.

But now, a team led by Rodney Ruoff at the Institute of Basic Sciences in Ula Liquid metal

The trip to this advance began with A 2017 study That showed a liquid gallium could catalyze graphene production from methane at low temperatures within a personalized vacuum system. Intrigued, the Ruoff team wondered if Gallium could also facilitate the growth of diamonds. His experiments initially involved sowing diamonds in Galio doped with silicon, but the results were inconsistent.

Then, during an experiment, the graduate student Yan Gong noticed small pyramids that formed on the edge of a diamond crystal. “That led us to understand that silicon was somewhat important,” Ruoff recalls. But add more silicon only produced silicon carbide, not diamonds.

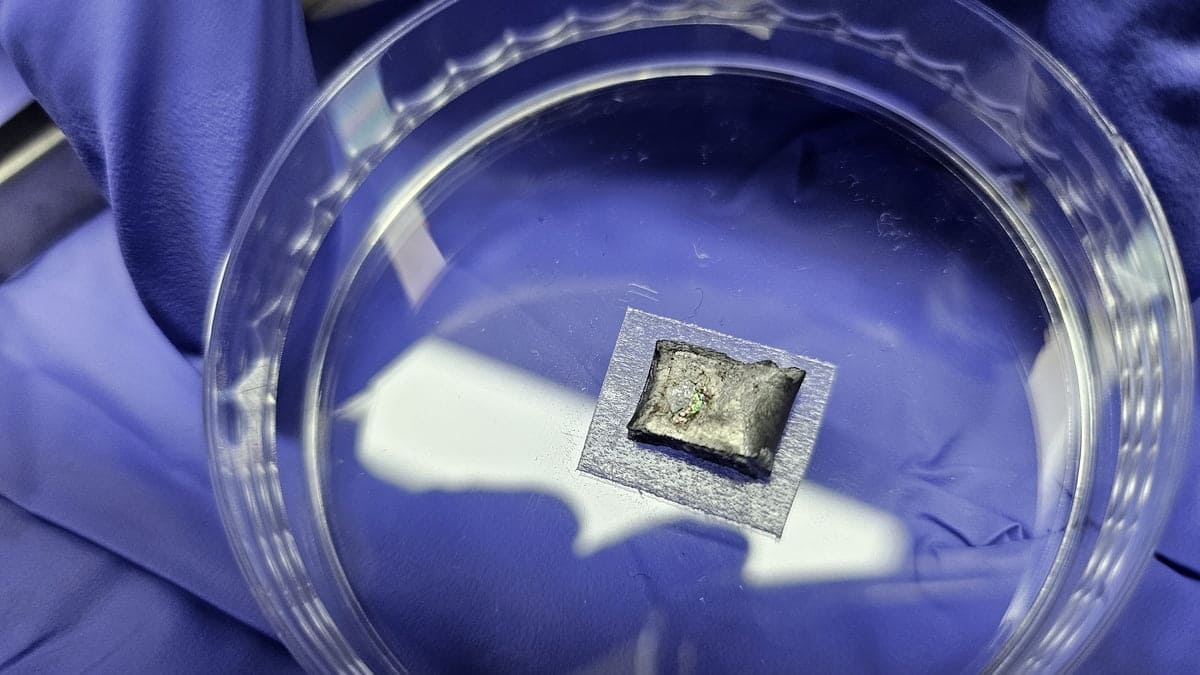

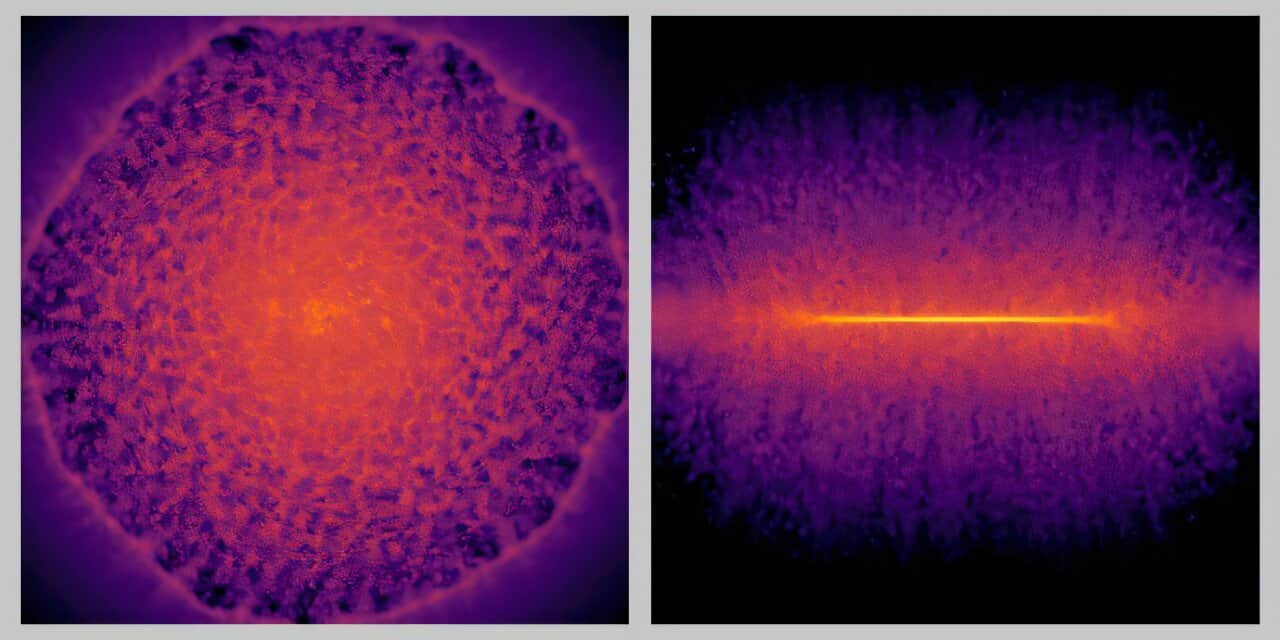

Without flinching, the scientists changed their approach, experiencing with an alloy of liquid metal composed of gallium, iron, nickel and silicon. After hundreds of parameter settings, they hit gold, or rather, diamond. Gong recalls the moment vividly: “One day, I noticed an extended ‘rainbow pattern’ on a few millimeters on the lower surface of the solidified liquid metal. We discovered that the colors of the rainbow were due to diamonds!

The science behind shine

The liquid metal method of the equipment implies exposing the alloy to a mixture of methane and hydrogen at 1.025 ° C. The carbon of methane is spread in the liquid metal, where it accumulates in a layer of thin and amorphous subsoil. This layer, rich in carbon and silicon, serves as the place of birth for the nucleation of diamonds.

“Approximately 27 percent of atoms on the upper surface of this amorphous region were carbon atoms,” says co -author Myeonggi Choe. High resolution images revealed that diamonds nucleate and grow in this layer, and finally merge to form a continuous film.

The process began with small crystals of isolated diamonds that appear after only 15 minutes of growth. Over time, these crystals became bigger and merged into continuous films. At 150 minutes, the researchers had produced an almost complete diamond film, with only a few remaining gaps.

Theoretical calculations suggest that silicon stabilizes small carbon groups, which act as “pre-nucleos” for diamond formation. Without silicon, diamonds did not grow, which suggests that it helps catalyze the formation of diamond crystals.

Implications and questions

Implications can be important. On the one hand, it could make diamond synthesis more accessible and affordable. Traditional HPHT methods require expensive equipment and consume large amounts of energy. The new method, on the contrary, operates at the pressure of the room and lower temperatures, which potentially reduces costs and energy consumption. Diamonds have exceptional thermal conductivity, hardness and electronic properties. These qualities make them ideal for use in high power electronics, quantum computing and even medical devices.

But many questions remain. Why does this specific combination of metals work? How stable are these diamonds? And can you refine the process to produce larger and more pure diamonds? Ruoff is optimistic. “There are numerous intriguing routes to explore,” he says.

The findings appeared in the magazine Nature.

#Scientists #cultivate #atmospheric #pressure #diamonds #liquid #metal #game #change