Here I am presenting a transcript of the first piece I wrote in the wordpress blog in 2008, and links to the other three parts of the very long explanation of the analysis.

Original part 1:

Original part 2:

Original part 3:

Original part 4:

—————————-

Of all the critics to my stand in the recent online discussion about the connection between Giromini’s and Arkani-Hamed’s papers, the only one who managed get me upset was Andrea, who argued that I was wasting my time on the issue, answering vacuous comments in the thread with vacuous objections, while it would have been much better if I spent it to discuss the CDF paper, about which I could maybe produce some useful details and insight for my readers.

The comment got me upset because Andrea was right, damnit. The problem is that the CDF paper discusses such a complicated analysis, and my time the last few days has been so limited, that I just was unable to do it; while answering comments is a duty which I cannot bring myself to neglect, and which after all can be handled with less concentration, bit-by-bit when I have small chunks of spare time.

Today, I want to start commenting on some aspects of the multi-muon analysis produced by CDF. I have little time to invest, so I will do a poor job. But maybe concentrating on a detail at a time may allow me to shed some light without saying just obvious things.

Now, we have learned that CDF is seeing an excess of muon candidates with abnormally large values of impact parameter.

What is a particle’s impact parameter ? Imagine you are shooting an arrow at a target, and imagine you miss the bull’s eye by a foot. That one foot is the impact parameter of the arrow’s path: the minimum distance between the arrow’s trajectory and the bull’s eye. Of course particles fly away from the point where protons and antiprotons collide, and not toward it: so the example is rather deceiving, but its ease of visualization makes it worth using it.

There are many other features of these weird events that require an explanation, but let us focus today on the very existence of these muon candidate tracks, in “ghost events”: ones that, by definition, have the muon apparently produced outside of the beam pipe, a 1.5-cm radius cylinder surrounding the beam axis inside the CDF detector. There are several possible sources of muon candidates with large impact parameter. These sources can belong to four distinct categories:

(1) ones that produce real muons with real large impact parameter;

(2) ones that produce real muons with badly measured impact parameter;

(3) ones that yield fake muons with real large impact parameter;

(4) ones that yield fake muons with badly measured impact parameter.

I will discuss class (2) in this post, but let me take (1) for a start, to make a few points. Real muons are a rare thing at a hadron collider, because they are the result of weak interactions, and weak interactions are rare in comparison to the strong interaction processes characteristic of hadron collisions. If we exclude a process called Drell-Yan (which is an electromagnetic process, but still relatively rare, and responsible only for an instantaneous creation of muon pairs, which thus have impact parameters compatible with zero) and the very distinguishable decay of W and Z bosons, all muons at a hadron collider are the result of the weak decay of hadrons: B hadrons (ones containing a long-lived b-quark), D hadrons (ones containing a c-quark), and lighter ones – especially kaons and pions, which are extremely frequent (tens per event, typically).

B hadrons are the most notable source of muons with large impact parameter: they disintegrate on average in 1.5 picoseconds, and by the time they do, they have traveled a few millimeters from the point where they are created -the primary interaction point. About 10% of the times, B hadrons produce a muon in the decay; and even when they do not, they produce particles which in turn may disintegrate producing a muon: all in all, about 23% of the times you should expect a B hadron to yield one muon track. So, B hadrons are indeed a source of real muons with large impact parameter: the B-hadron-originated muon does not, in general, point back to the proton-antiproton interaction point, any more than a bit of an exploding grenade is emitted in the same direction of motion of the grenade before the explosion.

The authors of the multi-muon analysis took great care to determine the fraction of the analyzed data (which is made by events which contain at least two muons) due to the production of B hadrons. There are several ways to do this, and I do not wish to discuss that issue here; indeed, the same CDF paper does not discuss the estimation of B hadrons in the data carefully, because this has been done in a previous publication by the same authors. In any case, the result is that B hadrons have no chance of explaining the presence of muons with impact parameters in excess of a few millimeters in CDF data. The B hadrons simply do not live long enough to travel that far.

Despite the lapidary sentence above, B hadrons do not just contribute to class (1) above, but also, in principle, to classes (2) and (3). This should not surprise you too much: real muons from B hadron decays might be subjected to reconstruction errors by the tracking algorithms, creating a badly measured impact parameter, resulting in a signature of class (2); and on the other hand, B hadrons do create many tracks with large impact parameter -not just muons- by means of their long lifetime, and if the tracks have even a slight chance of mimicking a muon, you get just that: fake muons with large impact parameter, class (3).

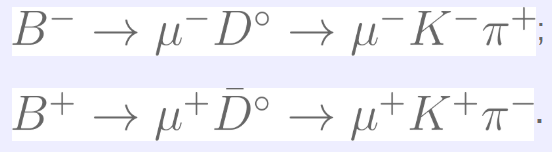

A problem with the tracking algorithm is not something easy to study with Monte Carlo simulations -these are to some extent idealizations which picture a rosier world than the intricate one we live in-, so the best way to check for the possibility of class (2) contributing to the signal of muons with abnormally large impact parameter is to use experimental data. A nice feature of B hadron decays is that when these particles contain a b-quark, their semi-leptonic decay may produce a negative muon and a charm quark; while when they contain a anti-b-quark, the decay yields a positive muon and a anti-charm quark. Oftentimes, the (anti)charm will bind into a neutral (anti)D meson, which soon in turn decays to a pion-kaon pair. We thus get the following decay chains:

By examining the two decay chains above, you immediately observe that the muon has the sign of the kaon. This makes a very good way to find out whether the “ghost” events behave like B decays or not: whether, that is, one can identify the muons in ghost events to B-decay muons which have badly measured impact parameters.

The authors have searched the detector close to their muon tracks for pair of oppositely-charged tracks which made a common vertex, thus reconstructing D0 -> K+pi decay candidates. In events where the muon originates within the beampipe (the subset of the data which should contain most of the B quark decays), one observes that when the muon and the track assigned to the kaon have the same charge, a prominent D signal appears in the invariant mass distribution of the pion-kaon pairs; while, when muon and kaon have opposite charge, no D signal is present: this is well-known and it in fact is a sanity check that allows to spot and size-up the B hadron content of the data. However, when “ghost” events are selected (ones where muons are produced outside of the beam pipe, i.e. farther than 1.5 centimeters from the beam line), no D signal is evident either in right or wrong sign combinations. What this tells us is that the muon in ghost events is not produced by B hadron decays.

The authors have searched the detector close to their muon tracks for pair of oppositely-charged tracks which made a common vertex, thus reconstructing D0 -> K+pi decay candidates. In events where the muon originates within the beampipe (the subset of the data which should contain most of the B quark decays), one observes that when the muon and the track assigned to the kaon have the same charge, a prominent D signal appears in the invariant mass distribution of the pion-kaon pairs; while, when muon and kaon have opposite charge, no D signal is present: this is well-known and it in fact is a sanity check that allows to spot and size-up the B hadron content of the data. However, when “ghost” events are selected (ones where muons are produced outside of the beam pipe, i.e. farther than 1.5 centimeters from the beam line), no D signal is evident either in right or wrong sign combinations. What this tells us is that the muon in ghost events is not produced by B hadron decays.

On the right are shown four K-pi invariant mass distributions in two panels. On the first one (above) you can see the D° signal appear as a gaussian bump on top of a large background in right-sign combinations (black histogram) in the track-track mass distribution, which contains “beam pipe muons”; wrong-sign combinations (red, hatched) do not have the D° signal, as expected. On the bottom panel, no difference is evident between right-sign (in black) and wrong-sign (in red, hatched) combinations: no D° signal is associated with “ghost” muons, underlining the fact that these events are not due to B decays.

On the right are shown four K-pi invariant mass distributions in two panels. On the first one (above) you can see the D° signal appear as a gaussian bump on top of a large background in right-sign combinations (black histogram) in the track-track mass distribution, which contains “beam pipe muons”; wrong-sign combinations (red, hatched) do not have the D° signal, as expected. On the bottom panel, no difference is evident between right-sign (in black) and wrong-sign (in red, hatched) combinations: no D° signal is associated with “ghost” muons, underlining the fact that these events are not due to B decays.

One comment is in order. This bit of the multi-muon analysis is maybe the least controversial among the complex chain of logical inferences which constitute it. There can be really no doubt that, among all the plausible sources of “ghost” events unearthed by CDF, B hadron decays cannot play a significant role. As I have had the occasion to mention in this blog elsewhere, particle physicists usually drop all objections when presented with clear, significant resonance peaks such as the one contained in the top graph above: those are the real “smoking guns” of the reality of elementary particles, and no argument holds against them!

In the next post of this series I will discuss another source of background to the tentative new-physics signal evidenced by the CDF multi-muon analysis: punch-through muons from kaon and pion decays.

#MultiMuon #Analysis #Recollection