A world of microbes lies within the intestine of each human being. This vast microbial community, the microbiome, which includes bacteria and viruses, has repeatedly demonstrated its ability to actively contribute to both health and disease.

Researchers have learned a lot about bacterial communities living in the human intestine. For example, they have discovered that these bacteria widely metabolize the food we eat, promote the normal development of the immune system and, to the detriment, include some opportunistic microorganisms that can cause diseases under certain conditions.

On the other hand, the contributions of viruses in the intestinal microbiome to health and human disease are not known to the same extent as those of bacteria. A new study published in Microbiology of nature This has changed.

The researchers of the Baylor Medicine Faculty have taken the initiative of a project to investigate whether certain viruses known as bacteriophages, or phages, which specifically infect bacteria but not human cells, affect the development of type 1 diabetes in young children. Because the phages exert pressure on the bacteria that infect and some phage genomes encode virulence and toxins, a role for phages or specific communities of phages in human health seems plausible.

“We believe that phages can affect survival or bacterial behavior and this in turn could influence human health,” said the first author Dr. Michael J. Tisza, assistant professor of molecular virology and microbiology in Baylor.

The current study resumed the samples collected as part of the environmental determinants of diabetes in the young study (TEDDY) with the objective of specifically outliearing the combined community of phanthings. The Teddy cohort was built with children at risk of developing immunity to cells that produce insulin and/or type 1 diabetes. Teddy’s previous studies investigated whether intestinal bacteria and human viruses affected the development of type 1 diabetes. Although they did not find a clear association with intestinal bacteria, there was an association with human viruses.

The phages are difficult to study

“Fago’s genetic data have been available for some time. We learned that phango genomes are very diverse, have few similarities between them and are very small, and they raised significant technical challenges for analysis,” Tisza said. “We approached the challenge by developing a new computational tool that allowed us to analyze the phage signals.”

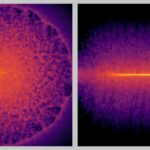

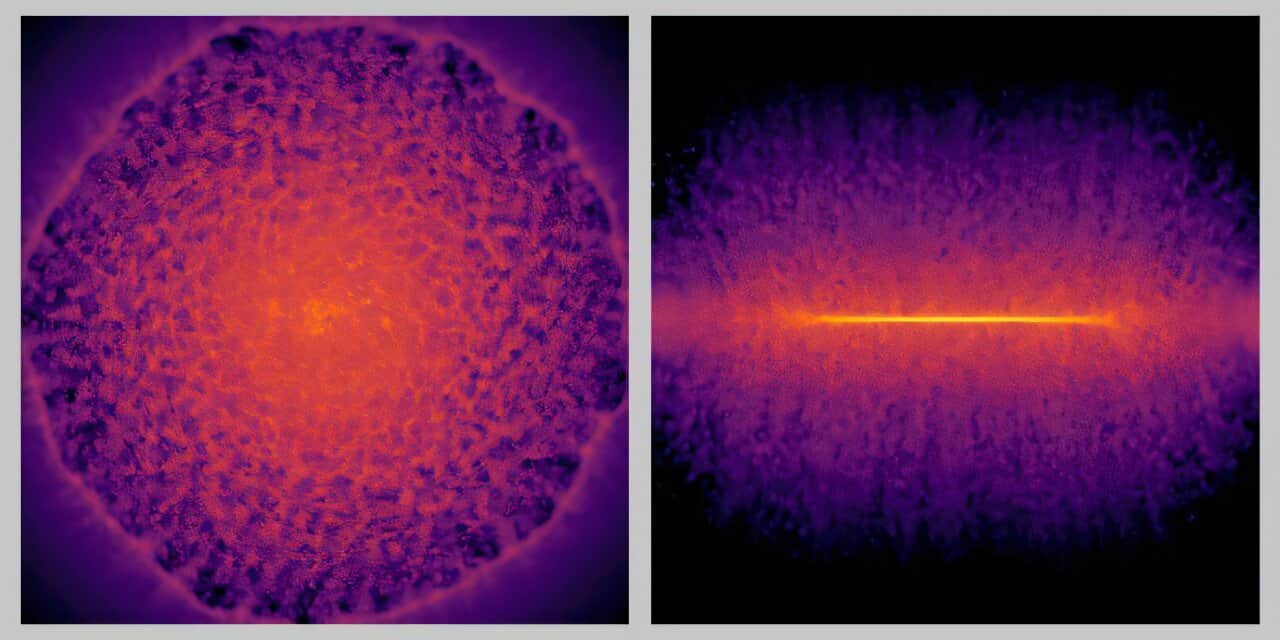

“Using our new analytical tool, we profile the combined communities of phage bacteria in 12,262 stool samples of 887 participants of the TEDDY study during her first four years of life,” said the co-closure author, Dr. Sara J. Javornik Cregeen, assistant teacher of molecular virology and microbiology in Baylor. “With this approach, we dissect the dynamic changes in the composition of the communities of phages and bacteria in the intestine in development and obtained new ideas about their interactions.”

The researchers found that certain bacteria thrive in different stages of human development, and this was observed similarly for phages in this study. “However, the rhythm at which the fago communities changed was faster than that of bacteria,” said Javornik Cregeen.

“We believe that this points to an arms race between the bacteria and their phages in which bacteria evolve acquiring mutations that allow them to escape the predation of the phages that infected them, and then that opens an opportunity for a new phage to infect the bacteria,” Tisza said.

With regard to type 1 diabetes, the team found no important communication of phages or phages linked to a greater or lesser risk of developing the disease in this cohort. However, the findings contribute to an improved perspective on the development of microbiome that reflects a dynamic interaction between phages and bacteria. The microbiome begins to develop as bacterial species enter the newborn child and begin to colonize the intestine. As the child grows, a succession of bacterial species remains in response to changes in diet and the development of the immune system. With this bacterial succession, phage communities also change, which reflects bacterial availability.

“As we analyze the microbiome many times during the first years of life, it was clear that the intestine of each participant is exposed to many more different phages than the different bacteria, which suggests that the immune system can be exposed to a more viral stimulation of what was previously considered,” Tisza said.

“We hope that our findings will result in a better understanding of the interactions of phage bacteria that can lead to better therapeutic approaches of the disease,” said Javornik Cregeen.

“The manipulation of the microbioma remains a promising path to treat a variety of diseases that involve the immune response, cardiovascular health and brain function, among others,” added the co-acorredor author, Dr. Joseph Petrosino, president and professor of molecular virology and microbiology and director of the Microbiome Research and Research of Microbiome in Baylor. Petrosino is also the director of scientific innovation of Baylor and a member of the Integral Cancer Center Dan L Duncan. “As doctors try to limit the use of unnecessary antibiotics as a main means to combat the increase in antibiotic resistant infections, studies such as this allow phage -based strategies to shape microbial communities to improve health and combat infectious diseases.”

Researchers are interested in continuing to explore relationships between bacteria and phages. For example, how phages influence the response of bacteria to disturbances such as antibiotics, change in diet or introduction of new bacteria. When evaluating temporary trends in the entrails of developing children, this study helps to lay the basis for therapy and diagnosis that aim to take advantage of the microbiome and its components.

Richard E. Lloyd, Kristi Hoffman and Daniel P. Smith in Baylor College of Medicine and Marian Rewers at the University of Colorado-Aurora are co-authors of this work.

#Understand #world #study #reveals #ideas #phage #interactions #bacteria #intestinal #microbioma