a new study in Nature Human Behavior led by Amy Caminoa research archaeologist from the University of Sydney, establishes that sites above 700 meters in Australia were inhabited during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), a period between 26,000 and 19,000 years ago. Way and his team discovered nearly 700 artifacts that provide evidence of repeated occupation dating back 20,000 years and connections to people from nearby regions.

The findings overturn the belief that the cold climate and sparse landscape at these elevations were barriers to survival on the continent. Throughout the research process, Way and the research team collaborated with Aboriginal communities who maintain traditional connections to the region, highlighting the importance of centering indigenous and local communities in archaeological research.

The LGM was the coldest period of the most recent ice age. At that time, in the Blue Mountains, temperatures above the periglacial limit (the altitude above which conditions were too cold and arid to support human habitation) were at least eight degrees Celsius colder than today. The tree line was hundreds of meters below the cave, leaving little firewood, and the water sources were frozen in the winter. Despite these conditions, the people who arrived at Dargan Shelter built homes, shaped tools, and transported stone from sources up to 150 kilometers away.

The excavation took place in Dharug Country, in the Blue Mountains, a region of great importance to many Aboriginal communities. The custodians of Dharug and other Aboriginal communities called Wiradjuri, Gomeroi, Darkinjung, Dharawal, Wonnarua and Gundungara maintain traditional connections to the land, and their knowledge and input was instrumental to the research. Wayne Brennan, Gomeroi knowledge holder, mentor in First Nations archeology at the University of Sydney and one of the authors of the study, initiated the research and helped secure the excavation permit.

The study’s authors excavated Dargan Shelter, a 1,073-meter-high cave in the Blue Mountains. Researchers and First Nations members discovered several hearths and 693 stone artifacts dating between 20,000 and 6,000 years ago. It is important to note that the collaboration with Aboriginal communities did not end with the excavation. The study promises that all artifacts will be returned to Dharug custodians, and that the Advisory Committee will “decide how they will be buried or displayed again.”

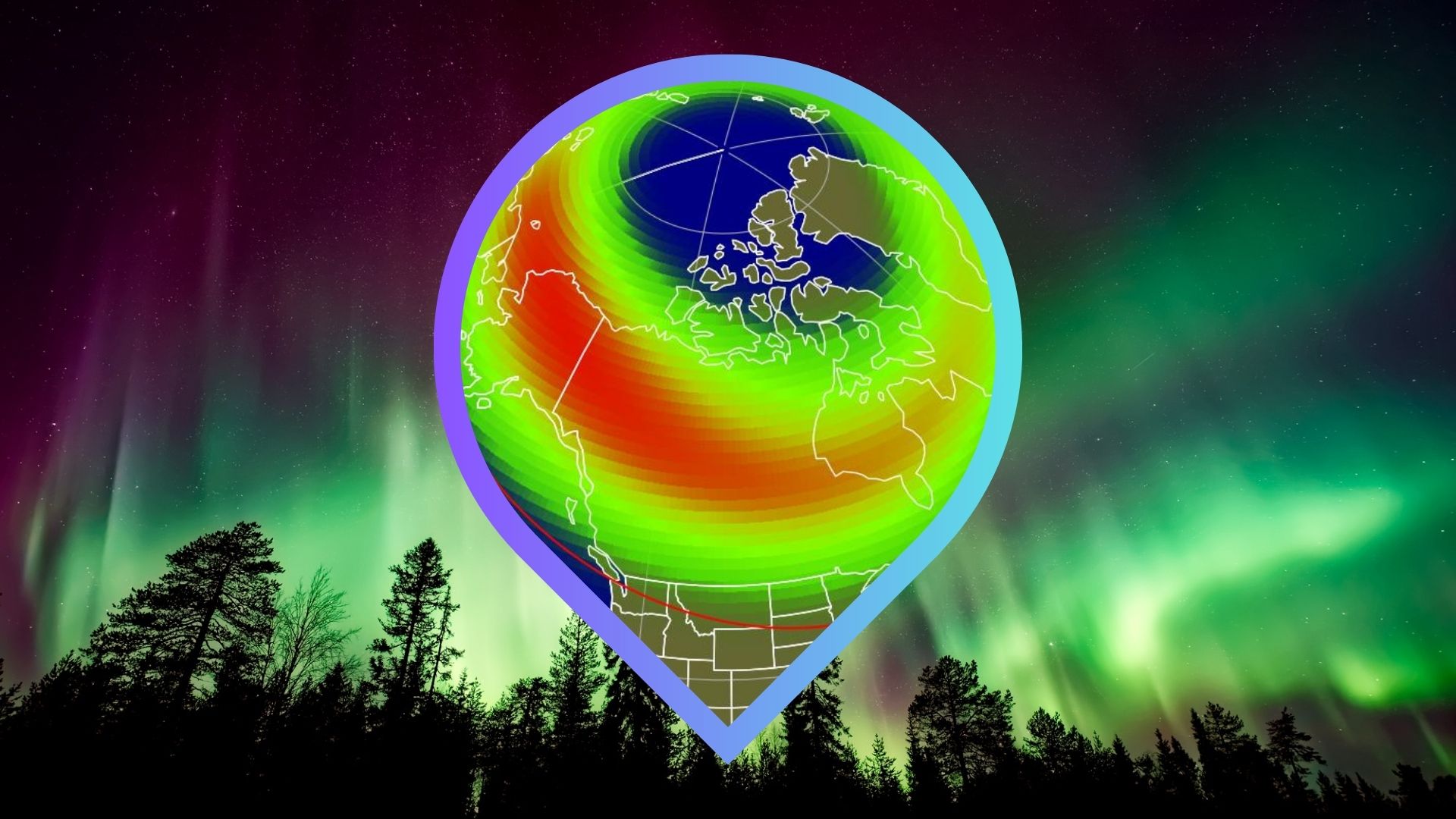

During the LGM, Australia had many periglacial sites (areas near glaciers that experience cold climates and short periods of freezing), whether in Tasmania, the Australian Alps or the Eastern Highlands, where the Blue Mountains and Dargan Shelter are located. Previously, evidence of human occupation during the LGM had only been found below the periglacial boundary, at sites in Tasmania and the Australian Alps. Finds from a Blue Mountains site suggested occupation above the periglacial limit, but the dating was disputed, leaving uncertainty about human occupation of the area before this 2025 study. Before Dargan Shelter, the earliest accepted finds of high altitude occupation in Australia dated to about 14,500 years ago. The Dargan Shelter excavation provides the oldest accepted evidence of such occupation, dating back to around 20,000 years ago, during the LGM.

Over three seasons in 2022 and 2023, Way and his team carefully removed layers of sediment to a total depth of 2.3 meters, recorded the location of each artifact in three dimensions, and sifted through the sediment to trap even the smallest ones. flakes— thin pieces of rock that are removed when making or sharpening stone tools.

Among the artifacts discovered was a sandstone slab dating back to about 13,000 years ago. The slab showed two grooves, probably worn when shaping and sharpening bone and wood tools that the cave’s inhabitants used to make leather clothing or jewelry, carve, or hunt. An 8,000-year-old stone anvil was also discovered, with impact marks suggesting it was used to open nuts and seeds. The team also found many heat-damaged artifacts and concentrations of ash and charcoal, indicating that homes were built and used during the occupation of Dargan Shelter.

Charcoal from the discovered hearths was radiocarbon dated, producing a timeline of repeated occupation from 20,000 years ago to just 330 years ago. Pollen analysis showed changes from treeless, tundra-like vegetation during the LGM to forests as the climate warmed. X-ray fluorescence analysis. He linked the chemical signatures of the stone artifacts to sources located up to 150 kilometers away from the cave, revealing long-distance mobility and connections across southeastern Australia. The study’s authors write that this evidence suggests that the region “may have been a stopping point for groups that spent a lot of time traveling along the mountain range during warmer seasons” to perform ritual practices or access certain resources. Brennan said The Guardian that the cave was probably a “guest house on the way to a ceremony site.”

Researchers paid close attention to Dargan Shelter’s stratigraphy (the study of layered sediments) throughout the excavation. Each layer of soil in the refuge represents a different period of human activity and environmental conditions. By documenting the position of each artifact within these layers, the researchers were able to construct a chronological sequence of occupation. The deeper deposits contained artifacts from the LGM, while the uppermost layers showed evidence of continuous use up to 330 years ago.

In an interview with GlacierHub, archaeologist Dylan Davispostdoctoral research scientist at the Columbia Climate School and the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, highlighted the rarity of the “degree of detail and number of acceptable radiocarbon dates across the entire stratigraphic sequence” at Dargan Shelter. Davis explained that “the level of preservation… is often a serious limiting factor in making definitive statements about the archaeological record,” so the preservation at Dargan Shelter is “quite impressive,” with more than 20 acceptable radiocarbon dates and showing a continuous sequence.

The Dargan Shelter sequence adds to recent findings in the Ethiopian Highlandshe Tibetan plateau, Spain and Mexicanco showing people adapted to high-altitude periglacial landscapes much earlier than previously thought. By documenting occupation above 1,000 meters during the LGM, this site places Australia within these broader cultural sequences and shows, Davis said, that “the landscape features we often think of as barriers did not actually prevent people from moving. This changes our understanding of Australia’s habitability and also forces us to reconsider such ideas in other areas of the world.”

The excavation of Dargan Shelter was carried out in close collaboration with the Aboriginal custodians of the Blue Mountains from the beginning. As noted in the study, it was initiated by Brennan and Way “to bring together local archaeologists and custodians to assess the cultural significance of previously unexcavated rock shelters in the Blue Mountains.”

A Blue Mountains Indigenous Advisory Committee was formed for the project, including representatives from six Aboriginal communities that maintain traditional connections to the region. The study notes that committee members were involved “in the design, implementation and reporting of project results” and approved all analyzes and excavations.

The Dargan Shelter study represents an important step forward in archaeological research. It places First Nations groups at the center of decision-making about their heritage and sets an example of how future climate history research around the world can be aligned with ethical and cultural responsibilities to communities. The study also aligns Australia with evidence of early high-altitude human occupation in the Americas, Europe, Asia and Africa, deepening our historical understanding of human movement and adaptation to periglacial and extreme environments.

#Humans #occupied #highaltitude #site #Australia #Ice #Age #study #State #Planet