Climate risk scores on real estate listings are having an impact on prices and real estate agents are complaining. But who should pay for these losses?

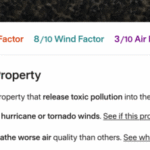

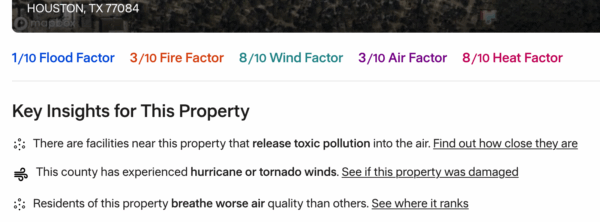

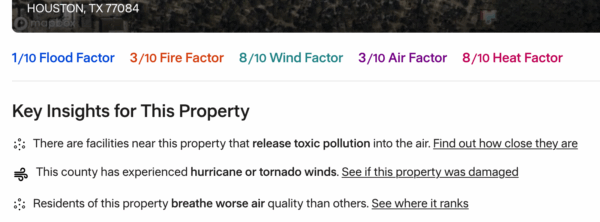

If you have been browsing Zillow either red fin In recent years, you may have noticed that (at least in the US), listings have been accompanied by a property risk score for fire, flood, air quality, etc. These scores have been generated mainly by first street – a private company that takes publicly available information on climate risk and reduces it to the batch level using a proprietary algorithm.

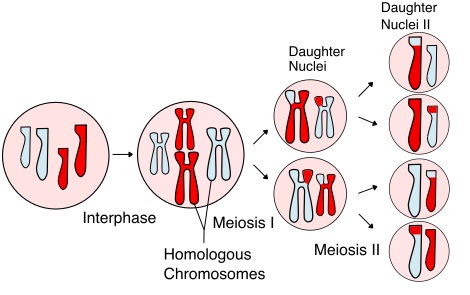

Below is an example of a house in Houston, Texas:

Since this has been common, analysts have noted that the lowest risk-rated homes are suffering. relative price declinesparticularly for homes at risk of flooding. This seems like a natural outcome: the greater the risk of flooding, the more expensive the insurance will be, and if insurance cannot be obtained, the greater the risk of financial loss and therefore there will be a price reduction to compensate. If this were a static situation, ideally these additional costs/risks would have been incorporated into the historical prices and the new prices would not have been worse affected. However, the situation is not static.

Heavy rains, forest fires, coastal flooding, etc. most common in many places (while air quality problems are declining), so the risks to properties are changing over time, and homeowners are realizing that they may not be able to sell their home for the price they expected. That’s a (relative) loss for those owners, for something that is not their fault (at least directly). Furthermore, lower (relative) prices mean lower (relative) real estate commissions and therefore this has upset the real estate industry also.

Actually, this is a big problem.

Sympathy for runners isn’t high outside of the industry (to say the least), and their struggles aren’t going to win many hearts or minds, but the bigger problem is much more serious. Climate changes will lead to greater future losses not only because more “things” are being built (a major factor in increasing historic damage), but also because existing properties face more risks.

For example, take a row of houses along the North Carolina dunes, one of which fell into the sea this summer. sea level there is growing (even more than the global average), predominantly a function of human impacts on the climate. Thus, a house built in 1976 that Zillow values over $400,000 Now it’s really worthless. There are many less extreme examples where increased rainfall intensity creates more flood risks, or increases in fires, etc., but the point is that the areas of greatest danger are expanding and, objectively, many property values are declining (relatively).

Generally speaking, rises and falls in property value are felt by current owners: they profit (when they sell) if an area becomes more desirable, or suffer losses if the opposite happens. Public policies can impact this, but primarily society addresses it through changes in property taxes and assessments (at least in the US). However, the impacts due to climate changes are different: these are changes that can, in fact, be attributed to our historical emissions that we have known for decades that they are having such an effect.

Previously, it was a situation like pass the package – whoever remained in possession of the property when the impact was felt (the flood, the fire, the sinking in the sea) would end up paying for it or, in the best of cases, sharing the losses with their insurance company. Information about risk factors helps distribute the costs among current owners (as well as future owners), which (I think) is a little fairer, but of course the costs are not borne by the people who cause the problem (the fossil fuel companies, the people who used their products, etc.). It has also been argued that society at large should cover these losses: that regional or federal governments, either through subsidies or insurance payments, should compensate homeowners, while others argue that oil and gas companies should pay.

There is a real problem as to how reliable these risk assessments are (if they are wildly different from different companies or approaches, or if the algorithms are proprietary, then the impacts of publishing this information may not be optimal. but both Florida (h/t Kelly Hereid) (for hurricane damage) and California (wildfires) are leading the way toward creating public, open-source catastrophe models, and that could possibly be disseminated more widely.

In practice, there will be a patchwork of different ideas and different models, but there is no (sensible) answer that relies on ignoring the risks of keeping prices artificially high. Even real estate agents should be able to accept that, and if they want to be compensated for lost commissions, they should get in line to sue the people who caused it.

References

-

CW Callahan and JS Mankin, “Big Carbon and the Scientific Case for Climate Responsibility,” Naturevol. 640, pp. 893-901, 2025. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08751-3

#RealClimate #pay