Originally from South America, the charismatic Tegu arrived in the United States through the pet trade in the 1990s. After wreaking havoc in Florida ecosystems, the exotic lizard was classified as an invasive species. But a recent discovery of the Florida Natural History Museum reveals that reptiles are not oblivious to the region: Tegus was here millions of years before their modern relatives arrived at pet carriers.

Described in a new study in the Paleontology MagazineThis advance came from a single fossil of mid -inch vertebra that was unearthed in the early 2000s and perplexed scientists over the next 20 years. Jason Bourque, now fossil coach in the Museum’s vertebrate paleontology division, found the peculiar fossil in the museum’s collection just outside the postgraduate school.

“We have all these mysterious boxes of fossil bones, so I was digging, and I kept finding this vertebra,” Bourque said. “I couldn’t understand what I was. I kept it for a while. Then I would come back and say: Is it a lizard? Is it a snake? In the back of my mind for years and years, it simply sat there.”

The vertebra had met in a clay mine of the land of Fuller, just north of the Florida border, after a local work team caused a visit from the museum’s paleontologists. There was only one capture: the mine was scheduled to close, and its quarry, along with any exposed fossil, it would soon be filled. Working against a deadline, scientists excavated as many fossils as they could and brought them back to the museum, where the vertebra sat down in storage, their unsolved identity.

Years later, Bourque stumbled upon an image of Tegu vertebrae while looking for studies for a new research work. “I saw the Tegu, and I immediately knew that this was this fossil,” said Bourque.

Today, the Tegus are of particular interest to the biologists and conservationists of the wild life of Florida. Their bold patterns and docile attitudes make them attractive pets, but that often changes once they reach almost 5 feet long and weigh 10 pounds. Exotic pets have a special ability to slide freely, or be released, in nature, where they can have a great cost in native ecosystems. This is the case with the modern Tegus in Florida.

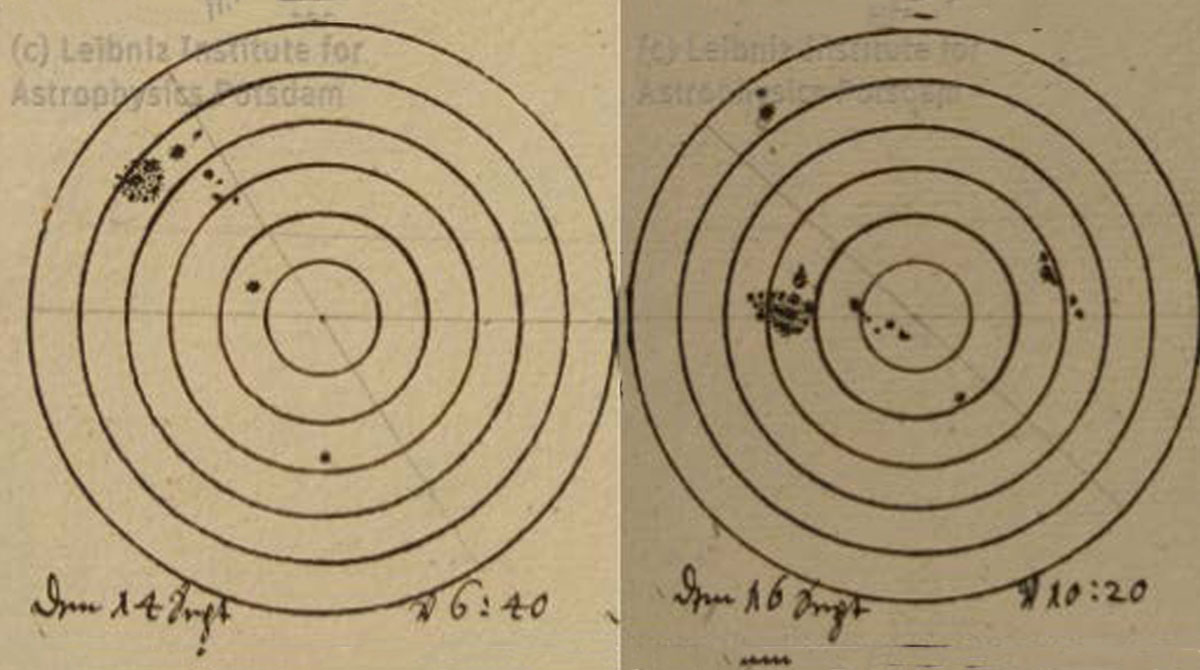

But until this point, there was no prehistoric Tegus record in North America. Bourque needed evidence to support his revelation. Paleontologists usually work with multiple bones to identify an animal, but Bourque has just had a single vertebra. He recruited his colleague, Edward Stanley, director of the Museum Digital Image Laboratory, who saw the opportunity to test a new automatic learning technique, one that does not depend on the decades of specialized knowledge of a paleontologist.

With a computerized tomography of the unidentified fossil, Stanley measured and carefully tracked every package, hole and fossil groove. Then, I needed vertebrae from other Tegus and related lizards to compare. Fortunately, the team had access to a large number of specimens thanks to the Openvertebrate (open) museum project, a free online collection of thousands of 3D vertebrate images. Instead of measuring these images by hand, Stanley used a technique developed by Arthur Porto, the artificial intelligence curator of the museum for natural history and biodiversity, to automatically recognize and adjust the reference points corresponding to more than 100 images of vertebrae of the database. When comparing the data in all its forms, he determined that the fossil coincided with the other Tegus and identified its original position with half of the lizard spine.

While the fossil was unequivocally a tegu vertebra, it was not an exact coincidence with any of the specimens in the database. This meant that the team had discovered a kind of news, which they named Wautaugateguru formidus. Wautauga is the name of a forest near the mine where the fossil was discovered. Although the origin of the word is not clear, it is believed that it means “Earth from beyond”, that Bourque and Stanley found appropriate for extinct species, which, despite having ancestral ties with South America, ended in current Georgia.

“Formidus”, a Latin word that means “warm”, refers to the reason why these lizards probably ended in the southeast of the United States first. The fossil is of the optimal climate of the Middle Miocene, a particularly warm period in the geological history of the Earth. At that time, the sea level was significantly higher than today, and with most Florida under water, the historical coast would have been close to the fossil bed site. The Tegus are terrestrial lizards, but they are strong swimmers. The warm climate may have tempted them from South America to current Georgia, but the region did not remain hospitable for a long time.

“We have no record of these lizards before that event, and we have no record of them after that event. They seem to be here only for an error, during that really warm period,” said Bourque.

The Tegus would probably have fought and, ultimately, disappeared as global temperatures cooled. Like other eggs of eggs, its reproduction depends largely on the temperature, and the cold may have limited its ability to produce or hatch eggs.

Finding more Tegu fossils can help demystify the brief period of prehistoric Lizard in North America. “I am ready to climb to Panhandle and try to find more fossil places along the old coastal crest near the Florida-Georgia border,” Bourque said.

Stanley, meanwhile, expects the next finding not to languish in storage. The combination of 3D modeling and artificial intelligence to identify fossils without depending on decades of specialized knowledge could drastically accelerate the process. With open access to data worldwide, it could even lead to a global database for fossil identification.

“There are full boxes, full of fossils that are not classified because it requires a lot of experience to identify these things, and nobody has time to look them in an integral way,” Stanley said. “This is a first step towards part of that automation, and it is very exciting to see where it goes from here.”

#prehistoric #resident #fugitive #pet #Tegu #Fossil