In the frozen sections of Greenland, a humble dog sits under a pale spotted sky. His breath makes small clouds in cold air. Its legs, wide and insensitive, press in the snow. This is the Qimmeq (or Greenland Dog), a special canine not for company or dog shows, but for resistance in some of the most implacable environments in the world. It is a dog destined to transport sleds through drifting ice, to smell stamps under the frost, to survive where few can.

It is possibly The oldest dog breed on earth. Its genetic history dates back to almost 10,000 years to Siberia. And for a thousand years, he has run next to the hunters of Inuit, not behind them.

A new study in Science Use ancient and modern DNA to tell the story of Qimmeq. It is a story not only about dogs, but also about people, migration and resistance. It is a story written in bones of bones and cheeks, which extends from the former Siberian tundra to the coastal settlements of modern Greenland.

A thousand years bonus

The researchers analyzed the DNA of 92 Greenland sled dogs, both alive and deceased for a long time. Taking into account the age of the race, the results turned out to be a true genetic time capsule.

“The Greenland Dog of Greenland is not just the brew of the oldest sled dogs,” says the main author Tatiana Feuerborn, paleogenetic of the National Health Institutes of the United States, “but it may well be the oldest dog’s breed.”

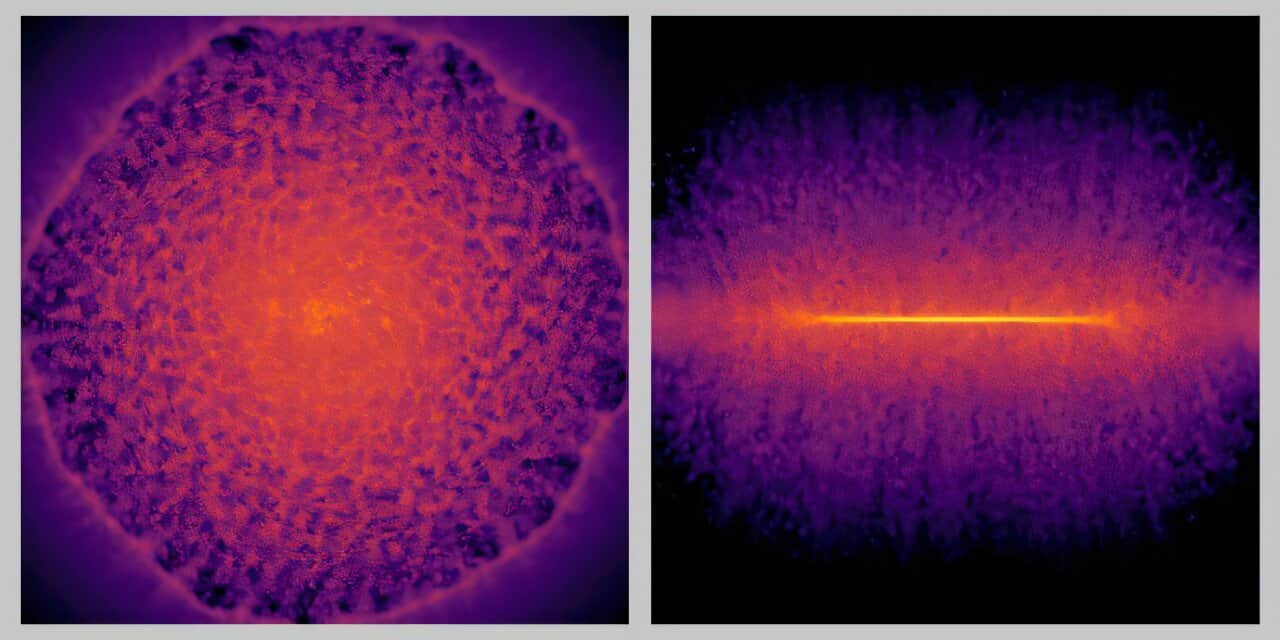

The research team gathered samples of archaeological sites, traditional clothing made of dog’s skin and even bell of modern mushers. Then they compared the genetic material of the Qimmeq with more than 1,900 genomes of published dogs. His findings show that Qimmeq has kept much of its original genetic identity for almost a millennium.

Most dogs, including modern sled races such as Alaska Huskies, have genetically mixed with other races. Qimmeq, however, is distinguished as genetically different.

“They are a work dog that has performed the same task with the same people for 1,000 years or more,” says Feuerborn. “That is what distinguishes them.”

Migration tracking through canine DNA

But the study is both dogs and humans. Because the Qimmeq traveled with Inuit migrants through the Arctic, its genes reflect that movement.

When mapping the genetic similarity between Greenland dogs and ancient dogs in Alaska and Siberia, the researchers concluded that the Inuit probably arrived in Greenland before what was previously believed, maybe up to 200 years before.

“This is one of the first quantifiable evidence that really gives it,” explains Feuerborn.

Their findings support a theory that the Inuit swept the Arctic of North America in a rapid migration of Siberia, crossing Alaska, moving through Canada and finally arriving in Greenland between 800 and 1,200 years. That migration, results, may have happened Before the arrival of the Nordic settlers.

Dog genomes also helped illuminate internal inuit settlement patterns within Greenland. Four main genetic groups in the populations of Qimmeq, North, West, East and Northeast, coincide with the distribution of indigenous Greenland communities.

Surprisingly, the Northeast dog DNA provides evidence of a human community that has otherwise faded from the historical record. There are few archaeological remains of these people, but the Qimmeq DNA remembers them.

Survival genetics

Dog genomes captured historical events, such as documented famines and mockery and rage outbreaks. During these crises, the population shrunk and Endogamue. However, the dogs endured. Even today, despite the acute decreases in their numbers, Feuerborn says they are genetically robust.

“They are actually really healthy dogs,” he says, although their population has collapsed from around 25,000 in 2002 to only 13,000 by 2020.

This collapse has many causes: melted ice, shorter winters, reduced hunting land and the arrival of snow motorcycles. Once vital, sled dogs are now being replaced by machines, so there is much less demand to raise them.

But snow motorcycles, as Feuerborn points out, “they cannot smell polar seals or bears. They are not silent. They cannot think for themselves. And they break down.” Sled dogs, on the contrary, are built for arctic survival. They are perfectly adapted to eat meat and cracks, endure extreme cold and run long distances.

Not even wolves or Europe eliminate the qimmeq

Feuerborn and his colleagues also explored a common belief among the Greenlandés: which sometimes crossed wolves to improve their resistance. However, your data does not agree.

“We were surprised,” says Feuerborn. Dogs did not show stronger genetic links with the wolves than other Arctic races. It is possible that Wolf-Dag hybrids simply have not passed their genes. If they could not perform the expected demanding tasks of sled dogs, they were eliminated.

Similarly, the Qimmeq resisted European influence. Despite the centuries of contact, including Danish-Noruega colonization in the 18th century, there is almost no European ancestry in its genes.

This level of genetic isolation is rare is our increasingly connected world, and makes the Qimmeq even more valuable, scientific and cultural.

“These ideas about the QIMMmit provide a baseline for the levels of endogamy and introgress that can serve as the basis for the informed management aimed at the preservation of these notable dogs,” the researchers wrote.

The greatest conclusion of the study is how closely intertwined the lives of humans and dogs have been. “Dogs have been as intrinsically linked to human history as the first domesticated animal,” says Feuerborn. “They have been in the formation of each human society.”

In Greenland, that association never ended and, in some places, it still looks the same as thousands of years ago.

But his future is uncertain. As the climate change reforms the Arctic, already measure that snow motorcycles take care of the work that once did, its numbers decrease.

#oldest #dogs #breed #reveals #humans #conquered #Arctic #heard