When a Guinea baboon gets hold of the meat, who eats it next is not a matter of luck, but of loyalty. After nearly 10 years of observing wild Guinea baboons in Senegal, researchers discovered a hidden rule behind every meal.

Published in a recent study in iSciencePrimates passed down meat not by chance but by closeness (first with family, then with favorite friends), a pattern similar to the exchange networks of ancient human foragers.

“We were able to show that Guinea baboons transmit meat through their social bonds,” said William J. O’Hearn, lead author of the study, in a Press release. “This form of tolerant sharing is reminiscent of the behavior of human groups of hunter-gatherers, where meat is first distributed within the family and only then reaches more distant acquaintances or neighbors.”

Parallels between baboons and ancient humans

Guinea baboons (Papio papio) live in complex, multi-level societies that closely resemble the organization of early human hunter-gatherers. At the base is the unit (roughly the baboon equivalent of a human family) made up of a male, several females and their offspring. Three or four units form a group, comparable to a human group of related families linked by long-term male friendships and kinships. Two or three groups then join together to form a gang, much like a human camp where different groups meet and interact.

Social bonds are strongest within units and weaken at each level, creating a layered network of cooperation. These parallels with humans suggest that some principles of social organization (from family trust to community-wide sharing) may have evolved similarly in both humans and baboons.

Read more: 300,000-year-old wooden tools suggest ancient humans also ate vegetables, not just meat

Monitoring meat exchange among Guinea baboons

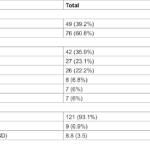

Between April 2014 and June 2023, researchers observed wild Guinea baboons at Senegal’s “Centre de Recherche de Primatologie” (CRP) in the Niokolo-Koba National Park. The team studied 61 men and 42 women, all adults or subadults, belonging to 13 social groups, eight of which were core study groups. Each baboon was individually identified using natural markings or radio collars, allowing scientists to track daily interactions.

During the study, researchers conducted thousands of 20-minute observation sessions, documenting grooming, resting and feeding, as well as every instance of capture or meat sharing. In 109 hunts, they recorded 320 transfers, from calm exchanges to aggressive steals. Most occurred through passive exchange, when one baboon finished feeding and another silently took its place without conflict.

Combining these field observations with statistical models, the team found that the closer the social bond, the more tolerant the exchange. Sharing was never deliberate; It arose naturally through social tolerance. Within family units, meat passed smoothly from one animal to another, while between groups it was scarce and strained.

What baboon behavior reveals about human evolution

The findings suggest that cooperation can arise naturally in societies built on stratified social ties. Even without deliberate generosity, Guinea baboons distribute meat in patterns that echo early human communities, a reminder that the roots of sharing run deeper in our evolutionary history than culture alone can explain.

“This suggests that certain social patterns may have developed independently in humans and non-human primates, but in a comparable way,” Julia Fischer, co-author of the study, explained in the press release.

Read more: Early humans were probably scavengers and ate remains of saber-toothed cats

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com We use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review them for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Please review the sources used below for this article:

#Guinea #baboons #share #meat #family #friends #early #human #foragers