Off the northeastern shores of Japan, a strange gelatinous creature recently appeared among the waves. Pale blue and semi-transparent, it looked like a jellyfish, until scientists realized it wasn’t. Instead, it was something potentially more dangerous: a kind of Portuguese warship.

Seen in Gamo Beach in Sendai Bay by a marine biologist Yoshiki Ochiaithe creature was sent to Tohoku University for analysis. What the researchers discovered was both unexpected and revealing. The specimen represented a new speciesgenetically distinct from any previously known warship organism.

they named him Physalia mikazukia reference to the crescent moon crest of the famous samurai Date Masamune. But more than a curiosity, its sudden arrival marked a potential biogeographic change—a tropical vagrant that occurs far north of its known range.

Its discovery has attracted attention not only for what it is, but for what it suggests: Warming oceans and changing currents are pushing poisonous marine life into uncharted waters.with unclear consequences for both ecosystems and human security.

New species, new territories

Unlike jellyfish, physalia They are not unique organisms. they are colonial siphonophores: groups of specialized zooids that function as one. Its long tentacles, equipped with stinging cells—help them catch small fish and zooplankton. And those same tentacles are capable of painful, sometimes dangerous bites to humans.

Until now, only Physalia utricleknown locally as “bluemouth”, which is usually found drifting near Okinawa. But P. mikazuki was found more than 2,000 kilometers further north in the Tohoku region—the northernmost record ever recorded for the genus.

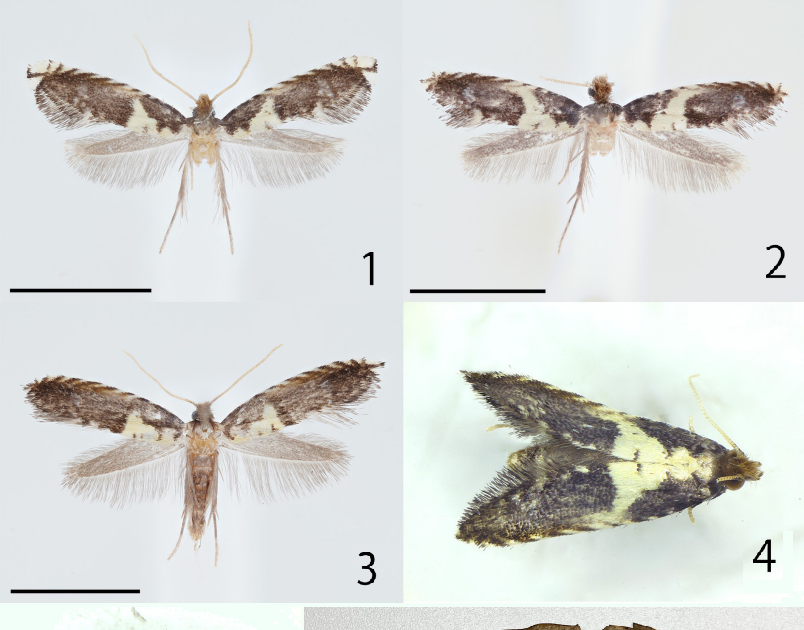

Genetic analyzes confirmed it as new lineageseparated from P. utricle, P. physalis, Megalist P.and the recently identified Minutes. Morphologically, P. mikazuki is defined by multiple primary tentaclesonly yellow gastrozooidsand a distinct ridge structure. These differences were detailed in the peer reviewed article which formally described the species.

“This is the first record of physalia in Tohoku,” the authors wrote. “The appearance of P. mikazuki in Sendai Bay highlights a significant biogeographic change.”

Ocean currents tell the story

Wearing oceanographic modeling based on data from the HYCOM (Hybrid Ocean Coordinate Model)The researchers simulated the possible migratory route of the new species. The results showed a possible northward drift trajectory from Sagami Baytransported by changing surface currents and rising sea temperatures.

Similar patterns have already been observed with the Nomura’s jellyfish (Nemopilema nomurai), a huge gelatinous predator that rarely appeared near Japan’s main islands, but has now become a seasonal threat to fishing and coastal infrastructure. as with P. mikazukiIts range has expanded along with climate-induced ocean changes.

According to the modeling in Borders study, P. mikazuki‘s presence aligns closely with long-term warming trends in the western North Pacific. In particular, the authors cite the increasing frequency of forays into warm waters and unusual wind driven drift patterns along the eastern coast of Japan.

The researchers also documented the sudden mass stranding of more than 30 P. mikazuki specimens along a 1.5 km stretch of coast. Local news coverage, including interviews with aquarium officials, noted that these strandings were unprecedented in the region.

A global pattern in disguise?

While P. mikazuki is recently described, it may not be geographically isolated. Genetic markers associated with the species have appeared in specimens from Mexico and Pakistansuggesting a wider transoceanic distribution. The team’s DNA analysis places him in a previously unclassified group:B2—within the world physalia phylogenetic tree.

This supports the findings of a 2025 study by Church et al., which identified at least five genetically different physalia speciessome of which had previously been grouped under P. physalis no clear type specimens. the existence of P. mikazuki further validates those ideas and emphasizes the hidden biodiversity of neustonic marine organisms (that move on the surface).

In it Popular mechanics articleThe research team points out that P. mikazuki may have gone unnoticed for so long because it overlaps in appearance with P. utricle. Their discovery was largely a matter of expert attention to subtle differences.

“These jellyfish are dangerous and maybe a little scary for some,” researcher Ayane Totsu said in an official press release cited by Popular Mechanics, “but also beautiful creatures that deserve continued research and classification efforts.”

#Researchers #shouldnt