The largest particle accelerator in the world, the great Hadron collider (LHC), is located in a circular tunnel about a hundred meters below the Swiss French border near Geneva. It is huge, some 17 kilometers of circumference, and capable of accelerating subatomic particles to the energies of 10^12 electronvolts (therav or tev), the highest ever achieved.

Built in the 1990s and went on to the bride and groom, the LHC is becoming old and the physicists now want to crush particles in even higher energies to see if something new arises from the remains. The problem is that these higher energies generally require longer tunnels to house larger and hungry accelerators of energy, which are difficult and expensive to build.

Therefore, physicists look for cheaper and smaller machines that can achieve greater energy in a small space and with a cost fraction.

Now Bifeng Lei at the University of Liverpool in the United Kingdom, and their colleagues, say they have resolved in principle how to achieve 10^15 electronvolts (Peta EV or PEV) on a device the size of a table. Its machine could pave the way for a new generation of compact accelerators that could help study the behavior of matter under ultra -high electric fields, relevant for both particles and astrophysics.

“This work represents a promising way for the development of ultra and high -energy particle accelerators,” they say.

Particle accelerators such as LHC operate repeatedly propelled particles charged through electromagnetic fields, gradually increasing their energy with each pass. The acceleration of loaded particles takes place within cavities full of powerful radiofrequency electromagnetic waves. Indeed, the particles accelerate by surfing in these waves.

However, powerful radiofrequency waves are difficult to generate, which requires costly superconducts cooled to the temperature of the liquid helium.

Another way to accelerate the particles is within a plasma. The trick here is to carve a route through the plasma using a laser or electron beam and then allow the loaded particles to “surf” in the resulting wake.

The so -called Wakefield accelerators are more compact and energetically efficient. But its acceleration power is limited by plasma density, which is generally a gaseous substance with less than 10^18 particles per cubic centimeter. That is significantly less than the density of free electrons in a metal that can be as high as 10^24 per cubic centimeter.

It is easy to imagine that metals should be excellent particle accelerators. However, physicists do not yet have x -ray lasers powerful enough to carve a path through such high density plasmas in metals, so they have not yet been exploited.

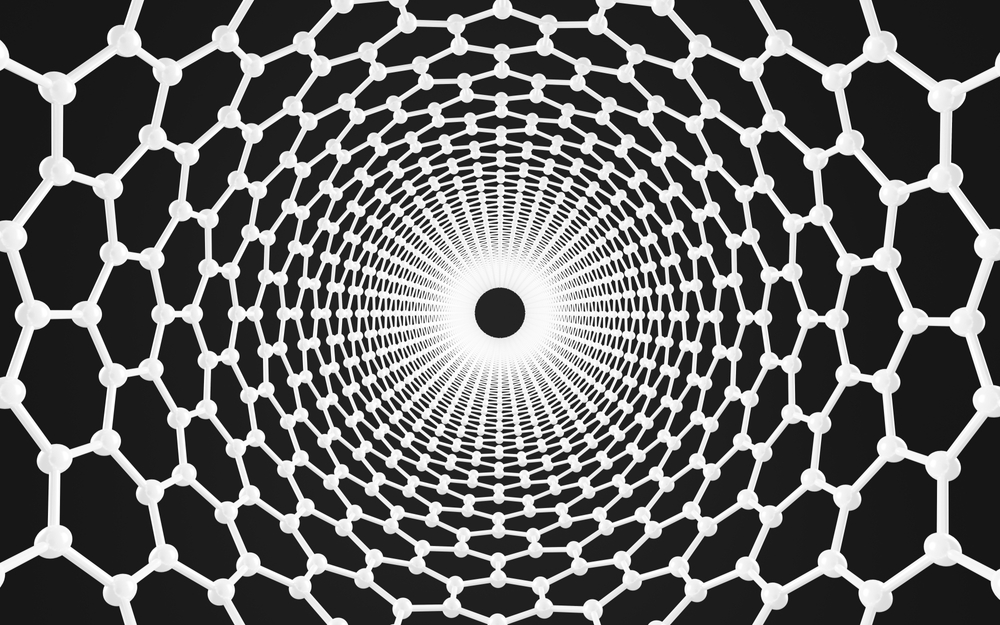

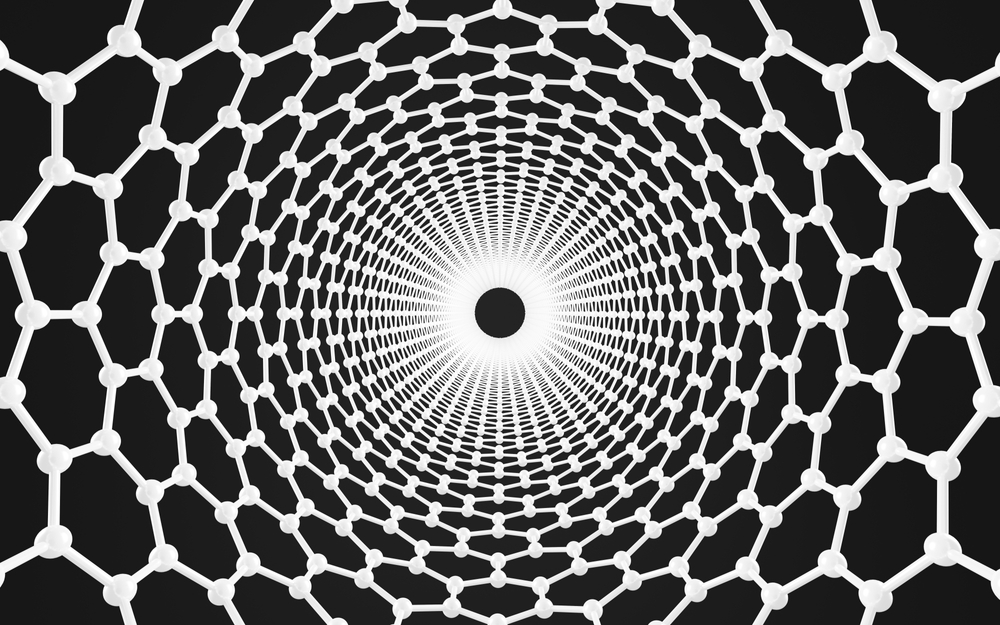

The advance they read and co made is to solve how to exploit similar plasma densities in a completely different material: a variety of carbon nanotubes.

In theory, the walls of carbon nanotubes house a sea of degenerate electrons that have a density similar to metals. But they also have a hollow and vacuum stuffed center in which electrons can move, if they are pushed with sufficient power.

Therefore, the materials that investigate consist of a variety of carbon nanotubes with an internal hole, such as a dry spaghetti package with some threads removed from the center to create a road at all times.

Then, the equipment simulates the effect of the transmission of an electrons pulse through this corridor, using the surrounding carbon nanotubes such as wave guides. The beam interacts with the electrons on the walls of the nanotubes, forcing them out as it passes and then returned to their original position later.

This establishes a powerful electric field within the carbon nanotubus that follows the electrons beam as it moves. It is this electric field that can accelerate other charged particles. This Wakefield acceleration mechanism, already explored in plasma -based accelerators, acquires a new and highly efficient form within the confined geometry of nanotubes.

In simulations, researchers show that this configuration can generate acceleration gradients in the range of hundreds of TEV per meter, magnitude orders greater than conventional RF accelerators, such as LHC. “In principle, electrons can be accelerated to PEV’s energies in distances of several meters,” says Lie and Co.

The team will map how the facilities currently available in CERN and other particle physics laboratories could be used to prove the idea in practice.

However, there are some potential limitations. One is that if the field inside the nanotubes is too large, electrons can be completely exploited and, therefore, do not return to their original positions and do not configure an acceleration field. Therefore, careful calibration will be needed to avoid such bursts.

Another is that researchers must create a highly compact and dense electron pulse to pass through the carbon nanotubes passage to begin with. The pulses of this density can soon be possible with state -of -the -art teams in the world’s leading particle physics laboratories.

If these experiments succeed, carbon nanotubes accelerators could revolutionize several fields. The powerful compact accelerators could allow new particle physics experiments without requiring infrastructure at kilometer scale.

Miniaturized accelerators could advance in radiotherapy for cancer treatment, providing electron beams or high energy ions with unprecedented precision. The same type of device could also be used for the advanced processing of materials, non -destructive tests and safety scan or even as a new propulsion technology for the spacecraft.

The enormously powerful electric fields within these machines could also allow physicists to reproduce conditions within certain astrophysical phenomena.

Lie and Co are optimistic about their potential. “The solid state plasma accelerator based on carbon nanotubes offers a transformative potential to advance in the development of ultra competent particles accelerators, opening new roads for several advanced applications.”

Ref: 100s Tev/M level particle accelerators based on carbon nanotubes driven by high density electron beams: Arxiv.org/abs/2502.08498v1

#Carbon #nanotubes #particle #accelerators #overcome #LHC