Throughout the world, the extreme climate is promoting a number of deaths, demanding billions in damage, threatening food and water safety and growing forced migration. However, some of the most sophisticated climatic models, vast computer simulations and complex climate system of the Earth, based on the laws of physics, are missing crucial signals.

Now, a research article published in Nature communicationsCo -author of the Postdoctoral researcher Feng Jiang; Climate scientist Richard Seager, the Palisades Geophysical Institute/Lamont Research Professor at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of the Columbia Climate School, the professor of Earth Sciences and Climate of the School of Cities (retired) has Key findings about why climatic models are getting many things wrong.

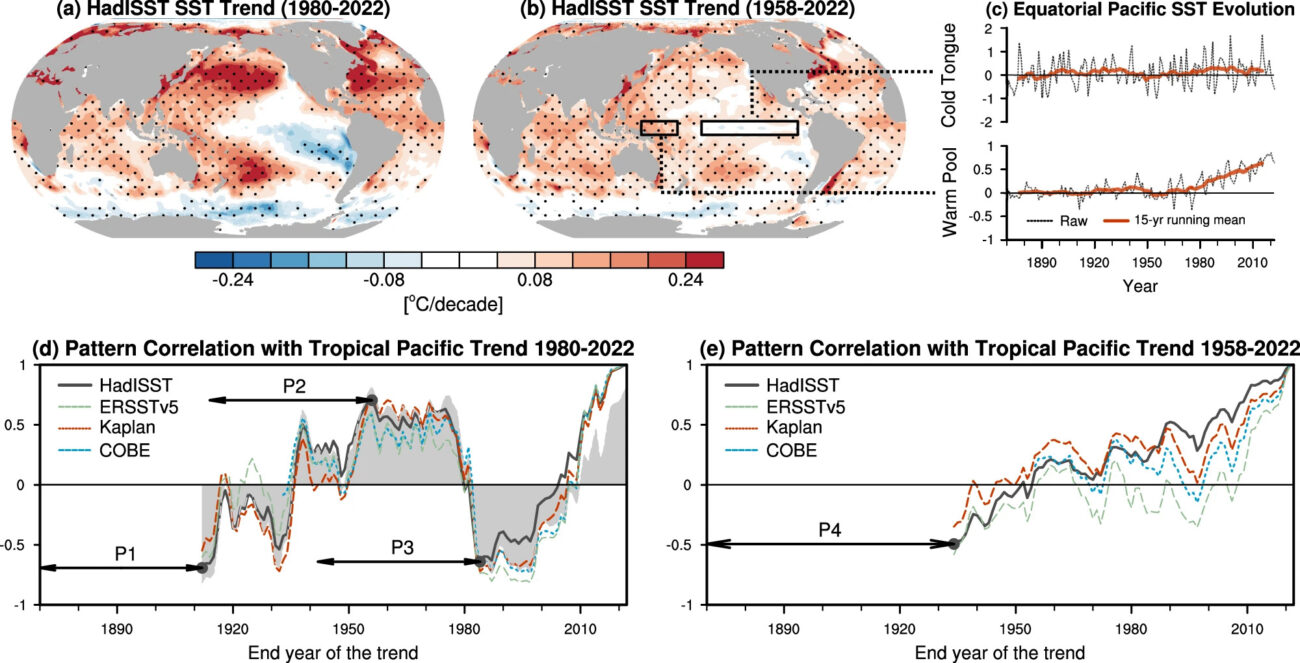

“Our work of Lamont is in the center of the debate in the community of climatic sciences and has caused climatic scientists around the world to rethink their models,” says Seaguer. “Discrepancy can be found in the Pacific Tropical Ocean. Specifically, the Equatorial Cold Language, ”explains Seager. The cold tongue is a strip of relatively cold water that extends throughout Ecuador from Peru to the Western Pacific, along a quarter of the circumference of the earth. It has been predictions by not heating the way in which generations of climatic models say it should.

“A cold language that does not heat up, while the rest of the tropical ocean means that it dries in southwest North America, East Africa, southeast of South America, but favors moisturizing in other regions such as the Amazon,” says Seager. “It also means more tropical cyclones in the Atlantic basin.”

To the incorrect trends in cold language temperatures, climatic models will also obtain projections of regional climate change in these and other incorrect regions. It is a discrepancy that has been observed for more than two decades. Many scientists believed that the natural variability of the oscillations of the southern El Niño masked the response to the increase in greenhouse gases and that eventually the Equatorial Cold Language would begin to heat up and align with the models. That has not happened.

“For 27 years, this discrepancy between models and observations is still there. In fact, it has become bigger over time, not smaller, ”says Seaguer. “It is beyond the time for the models to improve to better capture the processes that govern the surface temperature response to CO2 in the tropical Pacific.”

The study shows, for the first time, that there are two patterns at work, one that is a natural variability and oscillates from tendency the study calls the pattern of climate change of the Pacific (PCC). Scientists argue that the emerging PCC pattern is the response of the Tropical Pacific Ocean to ascending CO2.

“Our findings establish a way to help climatic modelers say the difference,” says Jiang. “The whole issue of how the tropical Pacific is responding to CO2 forcing is a big problem for regional climate change and even how much climate warming we will experience.”

Jiang and Seager say that there is not much work to do. But this latest research has an important orientation for climatic modelers and indicates the need to address long -standing bias when simulating emerging patterns, particularly in the cold language region, to improve the projections of regional and global climate change and its impacts and its impacts In the extreme climate.

#climate #change #sign #tropical #Pacific #planet #status