One of my students at Bentley University put it clearly the other day: “AI taking entry-level jobs is a ‘when,’ not an ‘if.’ But in venture capital, 70% of the decision is up to the founder and the team, and that’s something AI can’t do.”

That simple breakdown (70% people, 30% product) flips the usual narrative around finances. For decades, finance was defined by numbers. Analysts lived and died by spreadsheets. Today, AI can run discounted cash flows, analyze a term sheet, and size a market faster than any junior associate. But if you talk to people in venture capital, they will tell you that math has never been the most important part. Numbers matter, of course, but the difference between betting on a future unicorn and losing everything is whether you can read the humans on the other side of the table.

AI taking over “crucial” jobs

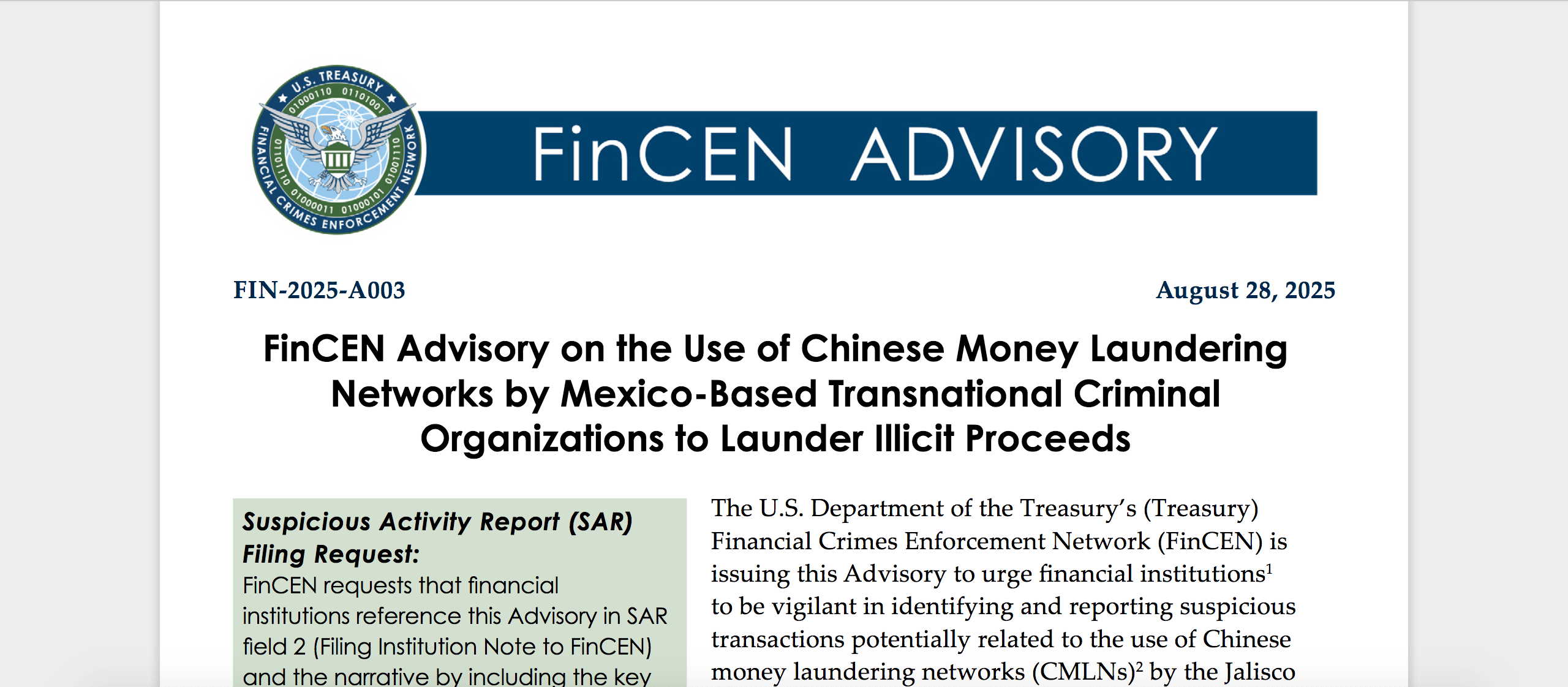

The students see what is coming. Entry-level finance roles that once trained armies of analysts are increasingly exposed to automation. AI models can scan thousands of comparable companies in seconds, create slideshows, and even point out anomalies that a first-year employee would have spent a weekend spotting. In fact, McKinsey estimates that almost half of financial tasks could already be automated with existing AI tools. What was once considered a rite of passage – the long hours hunched over Excel – may soon seem as obsolete as the typewriters in an accounting office.

That’s why many of the students I teach not only worry about Yeah AI will change your jobs. They assume he has already done it. The conversation now is how to build careers in finance when machines are better, faster and cheaper at the same tasks that used to get you in the door.

The venture capital exception

Venture capital, especially in the early stages, offers a counterintuitive lesson. Math can only take you so far. Market size, revenue projections, even technical due diligence – all are valuable, but nothing predicts success like the founder does. The investors I have spoken to express it bluntly: they are betting on people, not just products.

That’s the essence of the 70/30 rule that my student repeated: 70% of the investment decision has to do with the team. Only 30% is about the idea. Surveys of venture investors support this claim. First Round Capital, for example, has consistently found that founder quality trumps product or market size in early-stage decisions. You want founders with resilience, persuasion, and the courage to pivot when the idea inevitably changes. AI can tell you the market you are targeting. You can’t tell whether this particular founder has the charisma to convince skeptical investors, the judgment to hire the right people, or the sheer stubbornness to keep going after three failed prototypes.

As one early-stage investor recently told me: “AI can show me a founder’s track record in five seconds, but it can’t tell me if they can read a room or take a hit. That’s still my job.”

Why Generation Z gets it

What surprises me is how quickly students are internalizing this. Instead of seeing their careers in finance as doomed, they are recalibrating. They want to be people who can build relationships, persuade others, and trust their instincts. They are preparing to not be number crunchers, but decision makers.

Class discussions discuss practices where AI already plays a role in deal selection. What they take away is not despair, but clarity. They see that the irreplaceable part of the job is not working with the models but reading the room. They know that AI may one day suggest which startup should succeed, but you won’t sit across from a founder at 11 at night, hear the tremor in their voice, and know if that’s nervousness or conviction.

Generation Z, often criticized for being “too soft,” may be better positioned than we think. They have grown digital. They understand the machines’ strengths, but they also see their limits. They are comfortable letting AI do the heavy lifting if it means their human skills increase in value.

Lessons for the future of work

This change should force us to rethink not only finances, but also the future of work itself. If venture capital is a case study, the lesson is that industries once defined by quantitative rigor may end up placing even greater value on qualitative judgment. Harvard Business Review has made a similar point, noting that as AI scales technical analysis, “soft skills” are quickly becoming the hardest skills to replace.

The irony is rich: the most numbers-driven fields may be those where numbers matter the least. And if that’s true, Generation Z could be the generation that brings humanity back into the financial world, not by rejecting technology, but by mastering what machines cannot.

Back to the 70/30 rule

That brings me back to my student. His comment wasn’t just about venture capital. It was about what comes next in finance, and perhaps beyond. If AI eats numbers, the real job will be reading people.

AI owns mathematics. But instinct—the judgment, empathy, and intuition that turns data into decisions—still belongs to us.

Eventually, algorithms will get faster, but the best investors will always pause, look across the table, and trust what no machine can calculate: the human pulse of possibilities.

#finance #owns #math #humans #instinct